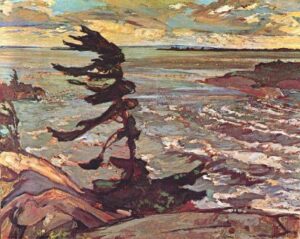

Tensions have flared a bit lately between the U.S. and our neighbors up north. I’ll steer clear of the politics, but it got me thinking: even the best relationships can go through a rough patch. Instead of focusing on the headlines, my mind turned to something more lasting that Canada has shared with the world—its art. Specifically, the Group of Seven. As a gallery owner who appreciates artists with a strong sense of place, I’ve always been drawn to their work. Their story is a great reminder that creativity has a way of rising above borders and bringing people together through a shared love of beauty and landscape.

The Group of Seven were a band of Canadian landscape painters in the 1920s who forever changed the course of Canadian art. If you’re not familiar with them, you’re not alone – many of us in the U.S. art scene might not instantly recognize their names. But in Canada, these artists are national icons. They’re celebrated for capturing the rugged beauty of the Canadian wilderness with a bold, fresh vision. In times like these, when political tensions flare even a little, the Group of Seven’s legacy reminds us that art can transcend borders and unite people through shared appreciation of the landscape we call home.

Who Were the Group of Seven?

In 1920, seven artists in Toronto officially formed what would become Canada’s first major national art movement, calling themselves the Group of Seven. They believed that Canadian art should reflect Canadian life and scenery, not just imitate European styles. These painters were largely friends and colleagues who worked together, hiked and camped together on painting trips, and shared a vision: to paint Canada’s landscape in a way it had never been painted before. They set out to develop a distinct Canadian artistic voice through direct contact with nature. Instead of the polished, European-influenced scenes popular at the time, they ventured into the wild—often literally by train or canoe—to sketch forests, lakes, and mountains firsthand.

The original Group of Seven consisted of exactly seven painters (more on each of them in a moment). They held their first exhibition in 1920 in Toronto, shocking some critics with their vibrant colors and modern style. Over time, their work gained recognition for its originality and emotion. Other artists would later join the group (A. J. Casson in 1926, Edwin Holgate in 1930, and L.L. FitzGerald in 1932), and influential painters like Tom Thomson (who tragically died in 1917 before the Group was formed) and Emily Carr (a west coast painter) were closely associated with their vision. But the focus has always remained on the original seven men who started it all. Let’s meet each of these founding members and see what they brought to the table.

Meet the Original Seven Members

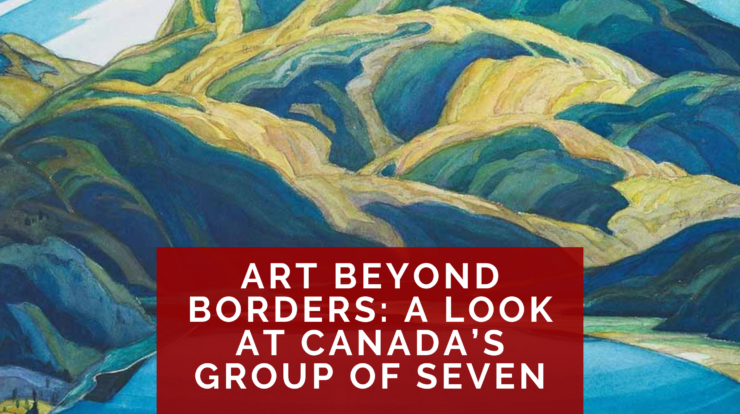

-

Mirror Lake –

Franklin Carmichael, 1929Franklin Carmichael – The youngest of the group, Carmichael was born in rural Orillia, Ontario in 1890. He was a skilled watercolorist and graphic designer. Carmichael had a knack for painting rolling hills, northern lakes, and autumn forests in luminous watercolors. His works often feature rich autumn golds and soft purples, capturing the gentle rhythms of Ontario’s landscapes. He also worked in oils and printmaking, but his transparent watercolor scenes (like tranquil lakes or dramatic cloudscapes) really set him apart. As a member of the Group of Seven, Carmichael brought a delicate touch and design sense – he could simplify a scene into flowing lines and shapes, conveying mood with subtle gradients of color. His vision helped prove that the quieter beauty of pastoral Canada was just as worthy of celebration as its grand vistas.

-

Decorative Landscape – by Lawren Stewart Harris Lawren Harris – Harris was the energetic leader and often seen as the philosophical backbone of the Group. Born in 1885 in Brantford, Ontario to a wealthy family, he could afford to fund artistic ventures – and he did, financing many group painting trips. Harris’s own paintings are perhaps the most instantly recognizable: he portrayed the far north and mountain landscapes with bold, simplified forms and a spiritual fervor. Think of smooth, rounded ice-blue mountains, clear skies, and sunlight breaking through clouds in a nearly divine manner. He had a way of reducing a scene to its essentials – a few strong colors and shapes – creating a sense of clarity and peace. Lawren Harris’s famous canvases of Lake Superior’s north shore and the Rocky Mountains have an almost otherworldly purity. He believed art should be an adventure and wasn’t afraid to push toward abstraction in later years. In the 1920s, his leadership and vision kept the Group of Seven pushing forward into new creative territory.

-

The Red Maple, 1914 – Alexander Young Jackson A. Y. (Alexander Young) Jackson – The extrovert of the group and a born traveler, A.Y. Jackson was born in 1882 in Montreal, Quebec. He had a friendly, down-to-earth personality and spent much of his life roaming the Canadian countryside with paintbrush in hand. Jackson’s specialty was capturing the charisma of rural Canada – from the charming villages of French Quebec to the rolling Algoma hills and the windswept shores of Nova Scotia. He painted in oils with lively brushwork and a love of color. His scenes often include rustic barns, red maple trees, or dramatic skyscapes, rendered in rich, warm tones. Jackson had served in World War I as an artist, and after the war he poured his energy into painting his homeland with pride. He was known to hop on trains or ships to reach remote areas to paint, whether it was the Yukon Goldfields or the stark Arctic coast. Through his adventurous spirit, Jackson ensured the Group of Seven’s influence spread far and wide. He also mentored younger artists and helped foster a sense of community beyond the Group itself.

-

Thunderers, 1920 – Frank Johnston Frank Johnston – Born in 1888 in Toronto, Frank Johnston was part of the Group’s early core, though he had a somewhat independent streak. Johnston’s landscapes are celebrated for their mastery of light and color, especially his winter scenes. Imagine a crisp winter day with sunlight sparkling on snow – Johnston could paint that brilliance beautifully. He often used vivid, clean colors and a somewhat smoother brush technique than some of his peers, giving his paintings a calm, reflective mood. During the Group’s famous painting excursions, Johnston impressed others with his ability to capture a scene’s atmosphere on the spot. He was a bit different from the rest in that he left the Group of Seven fairly early (after their first few exhibitions) to pursue his own path – even adopting the name “Franz Johnston” professionally. He moved to Winnipeg for a time to head an art school and mounted his own successful solo shows. While his time with the Group was brief, Johnston’s contributions (particularly his luminous wilderness scenes and snowscapes) added a touch of serenity to the Group’s body of work.

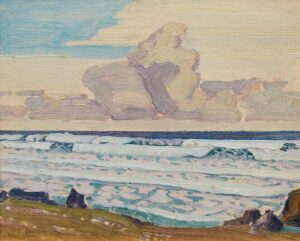

-

Isles of Spruce – Arthur Lismer Arthur Lismer– Lismer was born in 1885 in Sheffield, England, and later immigrated to Canada, bringing with him a sharp wit and a passion for teaching. He was the warm, jovial spirit in the Group of Seven, known for his sense of humor and lively personality. As a painter, Arthur Lismer loved dramatic composition – his canvases often show gnarled pine trees clinging to rocks, turbulent skies, and waves crashing onshore (inspired by his time in Nova Scotia during WWI). One famous Lismer painting, for instance, shows a tempestuous gale on Georgian Bay with trees bent in the wind. His style was bold and rhythmic, capturing the energy of nature. Beyond painting, Lismer made a huge impact as an art educator: after the Group’s early years, he devoted much of his career to teaching art to children and adults, and even directed art schools (including in Montreal later on). He believed art was for everyone, and that enthusiasm shines through in his work. Lismer’s presence in the Group of Seven added a dose of creativity and community spirit – he reminded everyone not to take themselves too seriously even while doing serious art.

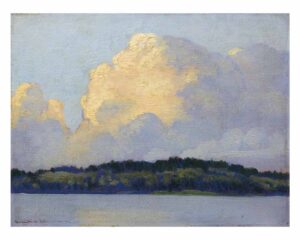

-

Surf, Barbados, B.W.I. – J.E.H. MacDonald J. E. H. (James Edward Hervey) MacDonald – The eldest of the group, J.E.H. MacDonald was born in 1873 in Durham, England, and moved to Canada as a teenager. MacDonald was something of a poet both in paint and on the page – he wrote poetry and was a talented calligrapher and designer in addition to being a painter. His paintings have a lush, romantic quality with deep colors and sweeping forms that make you feel the emotion of the landscape. MacDonald loved painting wild gardens, tangled undergrowth, and northern lakes with equal passion. One of his early famous works, The Tangled Garden, was bold and almost overgrown – a statement that Canadian nature could be vibrant and untamed. He also painted magnificent scenes of the Algoma region (northern Ontario), full of fall colors and rugged terrain. MacDonald’s compositions reveal his background in design: they often have strong patterns and decorative elements, almost like nature arranged as art. As a senior member, he was a mentor to the others and insisted that Canada’s raw beauty deserved its own artistic expression. Later, he became a teacher and even served as principal of the Ontario College of Art, influencing a new generation. Within the Group, MacDonald’s thoughtful, reflective approach and his commitment to a national art set the tone for what the Group of Seven stood for.

-

Stormy Weather, Georgian Bay – Frederick Varley Frederick Varley – Varley, born in 1881 in Sheffield, England (like Lismer), was the Group of Seven’s resident bohemian and an accomplished portrait painter. Among the seven, Varley was the one most interested in the human figure – he had done haunting portraits and even served as an official war artist during World War I, recording the grim reality of battle in paintings that still resonate today. When it came to landscapes, Varley brought a very emotive, atmospheric style. His best-known landscape works convey mood through dramatic use of color and vigorous brushstrokes – for example, his painting of stormy weather on Georgian Bay is full of dark swirling clouds and restless water, reflecting a bit of his own brooding personality. Varley had a strong classical art training, but he wasn’t afraid to experiment with vivid, almost expressionistic color in his art. After the Group’s early years in Toronto, Varley moved to the west coast and painted the soaring mountains of British Columbia, giving them a mystical, blue-hued treatment. He was always exploring the boundaries between realism and feeling. Varley’s presence in the Group added a touch of humanity and intensity, reminding the others that art wasn’t just about pretty views but also about expressing deeper feelings. His independent spirit (and occasional disagreements with the more conservative members) ensured that the Group of Seven never became too complacent or uniform in style.

(It’s worth noting that Tom Thomson, though not one of the seven official members, inspired them all with his passionate plein air sketches of Algonquin Park. Thomson’s sudden death in 1917 was a huge loss, but the Group carried his flame forward. Similarly, Emily Carr on Canada’s west coast shared the Group’s vision, painting the forests of British Columbia and becoming an ally in spirit. Others like A.J. Casson joined the group later. But the seven artists above are the founders who started the revolution.)

A Bold New Style Born of the Canadian Wilderness

So what was so special about the art of the Group of Seven? In a word, energy. These artists broke away from the gentle watercolors and polished European-style landscapes that had dominated Canadian art galleries. Instead, they delivered punchy color, bold brushwork, and a direct response to nature. When you stand in front of a Group of Seven painting, you often feel the crunch of snow underfoot, the glow of a sunset, or the whipping wind on a lake shore. They wanted you to experience Canada’s outdoors as they did.

Some common threads ran through their diverse styles. Vibrant color is one: they weren’t shy about using high-key oranges, yellows, and blues to exaggerate the drama of a scene. A swampy northern marsh might burst into a symphony of gold and rust in a J.E.H. MacDonald canvas, or a row of autumn birches might shine stark white against a violet hill in a Harris painting. Expressive brushwork is another hallmark: you can often see the brush strokes or palette knife marks, creating texture and movement. Look closely and you’ll notice the way paint is layered thickly in some areas and swept thin in others, giving life to clouds and rocks.

The Group of Seven also practiced a kind of simplification of form. This doesn’t mean their paintings were simple; rather, they distilled landscapes to their essential shapes and patterns. Instead of painstakingly rendering every leaf on a tree, for example, they might paint the whole tree as a single bold shape with a few dashes of highlight to suggest leaves. This approach was influenced by modern art trends of their time (like Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, which encourage artists to paint the feeling of a moment rather than every detail). It was also influenced by their backgrounds in design – many of them had worked in graphic design and illustration, which teaches you to compose an image dynamically. The result was landscapes that felt fresh and modern, even a bit abstract at times, while still undeniably representing real places.

Another key aspect of their style was plein air painting – painting outdoors on site. These guys weren’t studio divas; they threw on hiking boots, carried sketching kits into the woods, and painted in the open air to catch the immediate impression of a scene. They would later turn some of those field sketches into larger studio paintings, but the authenticity of having been there in nature gives their work a special honesty. You can almost smell the pine trees and hear the river in their paintings because, in a sense, those experiences are embedded in the art. Painting outdoors also meant they had to work relatively quickly (weather and light change fast), which led to spontaneous brushwork and a focus on big shapes over tiny details. This technique injected their canvases with the spirit of the moment – be it a tranquil summer afternoon or an approaching storm.

Stylistically, each member had his own flair (as we saw in their profiles), and interestingly the Group of Seven never imposed a strict style uniformity. What united them was more of an attitude: paint what moves you about your country, in whatever style feels right to you. They had seen contemporary Scandinavian painters doing something similar in their homelands, and it emboldened them to do it in Canada. The Group collectively proved that Canadian art could be adventurous, contemporary, and deeply rooted in Canadian soil all at once.

Impact on Canadian Identity and Artistic Independence

It’s hard to overstate the impact the Group of Seven had on Canadian culture. Before they came along, Canada’s art scene was seen by many (especially the establishment in the early 1900s) as a bit of a provincial backwater. Wealthy Canadians still preferred European paintings of English gardens or Italian villas – as if our own landscapes weren’t good enough for the walls of serious collectors. The Group of Seven turned that notion on its head. They asserted, through their paintings, that the Canadian wilderness held a beauty as grand and worthy as anything abroad. In doing so, they sparked a newfound sense of pride in Canada’s natural heritage.

Their 1920 debut exhibit in Toronto didn’t cause an overnight sensation, but it planted a seed. Some critics were baffled or even scornful, calling the paintings crude or too “modern.” (Legend has it one critic dismissed MacDonald’s lush Tangled Garden as “an attack of indigestion after a tomato salad” – a witty but snide remark on its wild color.) However, others saw promise, and importantly, the Group members believed in themselves. They kept exhibiting each year, and as the decade went on, public opinion shifted. People started to get it: these paintings weren’t distorted or odd for the sake of it; they were honest. They felt authentically Canadian – capturing the look and feel of the shield rock, the snow-laden spruce, the autumn blaze of maple leaves, and the shimmering northern lights.

By the late 1920s and into the 1930s, the Group of Seven’s work was being displayed internationally and was embraced at home. They effectively launched the first Canadian art movement that gained world recognition. It suddenly became cool to be a Canadian artist with your own style, rather than imitating European masters. The Group paved the way for future generations – they inspired the formation of new artist groups, like the Canadian Group of Painters, and influenced artists such as Emily Carr, who carried the torch in western Canada. Today, the Group of Seven’s paintings hang in every major Canadian art museum, and many Canadians grow up learning about them as part of their heritage. Their art has appeared on postage stamps, in school textbooks, and even on the currency (if you’ve ever seen the old Canadian $20 bill that had a scene of mountains and trees – that was inspired by their work).

Beyond the realm of art galleries, the Group of Seven helped shape Canada’s national identity. In the 1920s, Canada was a young country finding its voice, having just come out of World War I and starting to step out of Britain’s shadow. These artists said, in effect, our land is unique and beautiful, and we’ll paint it our way. This spirit resonated with Canadians who were eager to distinguish themselves culturally. The Group’s focus on the northern wilderness also fed into a wider cultural idea of Canada as a land of vast, pure nature – an identity Canadians, to some extent, still cherish. (Of course, this narrative wasn’t complete – Indigenous peoples had cherished and painted the land for millennia, though the Group of Seven didn’t really engage with that aspect. But at the time, the notion of a settler society forging its own art was front and center.)

Importantly, the Group of Seven also demonstrated a model of artistic independence. They weren’t sanctioned by any academy or patron when they started. In fact, they risked criticism and financial instability by pursuing their style. But their eventual success showed young artists that staying true to your vision can pay off. Canada, thanks in part to them, ceased looking always to London or Paris for approval in the arts. Instead, Canadian artists could be proud of their own school of painting. In a way, the Group’s legacy is not just the canvases they left behind, but the confidence and boldness they instilled in the artistic community.

Fast forward to today, and even amid the occasional political tensions between the U.S. and Canada, art remains a common ground. As an American, I can stand in front of a Lawren Harris painting of Lake Superior and feel the same awe as a Canadian would. Great art creates shared experience. The Group of Seven’s works continue to speak across borders – they certainly inspire me, and many American landscape painters I know tip their hat to the Group’s influence, whether they realize it or not. Every time we celebrate the natural beauty of our own regions in art, we’re following a trail that the Group of Seven blazed a century ago.

Lessons from the Group of Seven for Today’s Artists

The story of the Group of Seven isn’t just history; it carries some timeless lessons for working artists (and honestly, for anyone in a creative field). As I reflect on their journey, a few key takeaways stand out that feel especially relevant now:

-

Stay true to your region: In a world where it’s easy to get caught up in global trends, the Group of Seven remind us of the power of focusing on your place. They proved that the forests, hills, and neighborhoods in your own backyard can be the source of profound art. For today’s artists, this means you don’t have to chase the “hot” scene in New York or London to make meaningful work. Look around where you live – what moves you? Whether it’s the desert vistas of Arizona (something I relate to), the rain-soaked streets of Seattle, or the rolling farmland of the Midwest, embrace your local inspiration. There’s something authentic and compelling about art that is deeply connected to where the artist is from. It carries an honesty that viewers anywhere can feel. Just as the Group of Seven made the Canadian wilderness their muse, you can elevate the character of your own region in your art, making it something universal.

-

Create community: One of the greatest strengths of the Group of Seven was that they were a group. They weren’t seven isolated lone wolves; they were friends who critiqued each other’s sketches by the campfire, encouraged each other when critics got them down, and even shared expenses to go on trips. This kind of camaraderie is gold for artists. In today’s context, creating community might mean forming an informal critique group, joining a local art collective, or simply finding a few like-minded creatives to share experiences with. Community builds confidence. When you have peers who understand your vision (even if their work is different), you’re more likely to take risks and grow. The Group of Seven had each other’s backs – when they faced harsh criticism, they faced it together, which made them resilient. So, whether it’s online or in person, seek out your “group of seven,” however that looks. As a gallery owner, I can attest that artists who network and collaborate often find more opportunities. Plus, it’s just more fun to share the journey. Art doesn’t have to be a solitary mountain climb; it can be a hike with good company.

-

Trust your own artistic perspective: Perhaps the biggest lesson from the Group of Seven is to have the courage of your convictions. These artists pursued a style and subject matter that many at the time dismissed. They were told Canadian scenes were unrefined, that their bold colors were unorthodox. If they had caved to those opinions, we’d never have the treasure of their work today. But they believed in what they were doing. For contemporary artists, the message is clear: listen to that inner voice that drives you to create, even if it goes against the grain of what’s currently popular. Experiment, develop your craft, and by all means learn from others – but when it comes to the vision, be a little stubborn about making the art that you want to make. It can take time to gain recognition (the Group’s fame didn’t happen overnight either), but originality and authenticity build a lasting legacy. In an age of social media, it’s tempting to seek instant approval, but staying true to your perspective will ultimately set you apart. As one Group of Seven member, Fred Varley, famously implied: “Chop your own path. Get off the beaten track.” Trust that you have something unique to say through your art, and keep at it.

Conclusion

Writing about Canada’s Group of Seven in the midst of a news cycle filled with tariff talk and political posturing has been a refreshing reminder of the enduring connections between our countries. Long after today’s disputes are resolved, the art of the Group of Seven will continue to speak to people on both sides of the border – and indeed around the world. Their paintings carry the spirit of Canada, but the themes of nature, friendship, and creative freedom are universal.

For me, as a gallery owner and art lover, the narrative of the Group of Seven hits close to home. It reinforces why we do what we do – why artists pick up a brush in the first place, and why viewers find meaning in paintings. It’s about expressing a love of place, forging your own vision, and maybe even challenging the status quo along the way. The Group of Seven did all that, and they did it with an honesty and passion that still inspires us today.

So the next time U.S.-Canada politics get a bit frosty, I might just pull out a book of Group of Seven paintings or visit a gallery and remind myself of the bigger picture – quite literally, those big, gorgeous pictures of lakes and pines and mountains that redefined Canadian art. In the grand scheme, culture and creativity have a longer legacy than any trade spat. The Group of Seven’s work has become a lasting bridge between people, one that invites us all to step into a northern forest, breathe in the cool air, and see the world through the eyes of artists who truly believed in their vision. And as we’ve explored, that vision carries plenty of wisdom for artists and admirers everywhere, including right here in the U.S.

Sources:

YES!

This is a fabulous inspiring article!

American artists have influenced us in Canada for so many years.. and it’s with great emotion that I thank you for helping those of us from both sides of the border to remember the power of great art.

Thank you for the article. Growing up in Toronto there was likely a framed print of these artists in every classroom. With summer camp in Muskoka, canoe trip in Algonquin Park, fishing and camping on Georgian Bay, I probably saw some of those trees or rock formations as a kid. My neighbor or neighbour, eh?, had a little art school in Muskoka in the 50’s or 60’s.

Great Article! Well researched and written..Thankyou. I have to confess I knew nothing of Canadian Art, (excepting some indigenous works seen at a small gallery in The Bronx years ago), I will now actively seek out these Seven (plus) Artists’ pieces in NYC. As a working Artist in New York for the last forty odd years I have always respected the work of The Ash Can School, who ,as you know, were approaching the immediate, intense environments of this City at it’s most transitional time, in the early 20th Century. Their ‘ En Plein Air ‘ Styles were as varied and vibrant as were these Canadian painters and remarkably they were active at around the same period…it is interesting to me to find out if these two groups new of each other’s work.

Thanks Again, I always enjoy your articles and videos and appreciate your dedication to working Artists.

indeed the group members knew of the new york groups and exchanged ideas and concepts as artists do today.

Before embarking upon the styles of the [group of seven] through plein aire painting of the ontario region most were graphic illustrators for the same company for many years. honing their skills through the commercial arts they came to understand the techniques of color seperation and simplicity of form. they wanted to create a style unique from both the hudson river school and that of the french fontanbleau artists. The style formed over decades of practice and then expressed once tom thompson came onto the scene. Only then did they view themselves as artists not illustratrators. from long association giving each other the freedom to express in their own forms which was a novelty in the day of formal trained schools who valued conformity.

As an artist have studied them and the style going out to the same areas to paint the same scenes. Have also owned numerous works over the years, some from ontario others from western canada that were done during expeditions later in their lives.

As it has done before the arts will last out the current trade wars and divisions. Speaking to a part of the human condition that is beyond the petty squabbles of commerce and egos.

A great article and a great read. This comes at a time I think many artists need to hear the comments about staying true to their vision, and not letting someone else dictate what everyone likes. Look around your area of the world and paint, draw, photograph or what ever your medium is, get it down for others to see.

What a superbly excellent treatise on the Group of Seven. As a Canadian with a major in American History, a student of Art History, (I also love the Ash Can School and post Great War periods,) a passionate landscape and architectural photographer and an active politically involved citizen who is very saddened by the current turn of economic events I fully appreciate the thoughtful comments you make about the universality of art and how it unites and not divides us.

Thank you for your initiative. It is much appreciated.

Thank you for your this wonderful article Jason. Art does bridge so much of human experience and wonder. It seems that within the borders of the personal painting and the artist’s visions the expressions are universal and continue to encourage us. Artist’s creations go beyond colours and shapes…and help us appreciate things in new ways by their sharing it. Thank you for sharing these artworks and your words.

I haven’t had a chance to read your post, Jason, but will do so as my husband and I drive from Canmore, Alberta to Denver on Sunday. What I want to say is that when I opened RedDotBlog just now, I became tearful at being reminded of what is happening between our two great countries at a political level. Most of us must surely recognize that as neighbours, we are just ordinary people who mix and mingle beautifully and care for each another. We mean no hardship or harm to one another. My husband and I have superb friends in the US and our three sons, their wives, and five grandchildren live there. Treaty NAFTA made it possible in the 90s for our grown boys to work there, and then, of source, to love there. It’s always wonderful to visit back and forth (although our Canadian dollar is the shitz these days but my granddaughter loved it when she was here visiting Banff and Lake Louise as well as attending an Oilers hockey game in Edmonton. And don’t forget the shopping!).

We’re all in this together and it WILL all work out. Thank-you for bringing our Group of Seven to the fore, Jason and the responses. I can hardly wait to read your post.

In Light & Love,

Verna Korkie

Hello Jason,

I love this article on the History of the Canadian Group of 7 painters. Their watercolors are painted with such purity of what they were seeing and painting. They were spiritually guided and therefore empowered.

Thank you Jason, your articles about Art are the best!!

Cecilia Gallagher

Thank you so much for this inspiring article, Jason. It is an excellent tribute to our Canadian heritage and shows such respect for our country. It is so very much appreciated at this sad and unnecessary time in our shared history. Who would ever have imagined that US-Canadian relations could take such a turn?

Your article touched my heart in so many ways.

It also encouraged me to keep painting and never give up hope on any front.

Merci beaucoup!

Gladys Symons

Mont-Tremblant, Quebec , Canada

A wonderful article Jason. I was introduced to the Group of Seven, and especially Tom Thomson’s paintings by a teacher several years back, and I’ve been an avid fan ever since. Your article has shed more light on the eight of them that I appreciate.

I’m very fond of Tom Thompson’s work. Thanks for introducing me to other Canadian artists exploring a similar vision.

You might be interested to see the work of Walter Anderson, a Mississippi Gulf Coast artist with a vibrant palette and a rhythmic sense of natural patterns. I have a Pinterest collection of work his work I’ve found around the web: https://www.pinterest.com/alecdann/walter-anderson/

Excellent blog! Not one of my art history classes ever mentioned the Group of Seven artists from Canada. I only came across them when researching some info for my students. I was so intrigued that I applied for and received a grant from my local art museum to travel to Canada and learn more. The Algonquin area in Ontario provided amazing landscape scenes. I was able to hike to many of them and bring small panels for some plein-air paintings. Hopefully these talented artists will eventually become more well known and included in art history.