Edmonia Lewis and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

There’s been a longstanding relationship between art and literature. From numerous works based on mythology to storybook illustrations to Millais’ Ophelia, artists have often taken inspiration from their favorite books and poems. However, very few artists have had the chance to meet the authors whose work has inspired them.

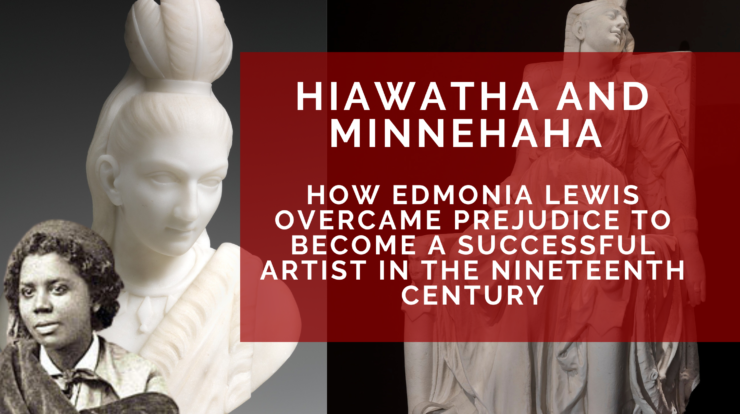

Edmonia Lewis was working in Rome when she began creating sculptures inspired by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Song of Hiawatha.”

An Unlikely Beginning for a 19th Century Artist

Having grown up in the pre-civil war United States as a free Black woman with Native American Ojibwe ancestry and now working in Italy, Lewis drew from multiple cultural traditions in her work. Many of her subjects were Black and Native American men and women, but she sculpted them in a Neoclassical style.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The busts of Hiawatha and Minnehaha are strong examples. While the characters they represent are from Longfellow’s epic poem, an interpretation of Native American history and folklore, they are sculpted to fit Western ideals. Lewis paid special attention to their draping clothing, giving them a Greco-Roman feel.

Lewis created the sculptures in 1868, and about a year later, she received a visit from Longfellow in her Rome studio, and he posed for a sculpture that is now in Harvard University’s collection.

Longfellow wasn’t the only influential American to visit Lewis’ studio. It became quite an attraction for American visitors to Rome.

Lewis received a lot of praise and recognition for her work during her lifetime. Unfortunately, she had to work against a lot of prejudice to get there. As a black artist, for example, Lewis had to be conscious of her stylistic choices, as her largely white audience often misread her work as self-portraiture. To avoid this, her female figures typically possess European features.

Still, she became a successful artist while representing her cultural roots, which were revolutionary for the late 19th century. Her busts of Hiawatha and Minnehaha ultimately ended up in the Met in New York.

Edmonia Lewis’ Early Life

It’s a little bit difficult to find accurate information about Edmonia Lewis’ birth and childhood since there aren’t a lot of official records and the artist’s accounts were sometimes inconsistent. One birthdate she gave was July 4, 1844, but it was common for Americans who didn’t know their exact birth date to claim Independence Day.

Lewis was orphaned when she was fairly young and was raised by her mother’s relatives. She went by the name Wildfire during that time, but she dropped it and added the first name, Mary, becoming Mary Edmonia Lewis, when she began attending Oberlin College.

Oberlin was one of the first universities in the United States to offer an education to women and people of color. However, Lewis still faced difficulties due to her gender and race. At one point, she was accused of administering non-lethal poison to two of her roommates and went to trial. The charges were dismissed, but not before Oberlin locals badly beat Lewis.

Later, Lewis was accused of stealing art supplies, and ultimately she left the university.

For a few years, she lived in Boston, mainly sculpting portraits of famous abolitionists and Civil War heroes.

From there, she was off to Rome. She later said, “I was practically driven to Rome to obtain the opportunities for art culture, and to find a social atmosphere where I was not constantly reminded of my color.”

The Death of Cleopatra

One of Lewis’ career highlights was the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, where she displayed her huge marble sculpture, The Death of Cleopatra, inspired by Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra.

When neoclassicism began to lose popularity in the 1880s, Lewis fell out of favor, and little is known about her final years other than that she moved to London, England, and passed away there in 1907.

Edmonia Lewis was a groundbreaking artist who overcame adversity to become successful. She was one of the first black women to attend college and one of the first black artists to achieve recognition in the United States and Europe. Her work was influential to many other artists, and she has left a lasting legacy.

What do you think of Edmonia Lewis’ sculptures? Have you had a chance to see them in person at the Met? What are some of your favorite works of art inspired by literature? Leave your thoughts in the comments below.

a life of adaption and survival getting around the attitudes of society. nothing too much as changed in the art world really.

Thanks for bringing Lewis’s work to our attention, I’d never heard of her before. If biases toward women exist in the art world I can happily say that I’ve never experienced them on a personal level. I’ve always felt accepted as an artist and don’t feel that my gender has been a negative thing. In the 80’s Janson’s ‘History of Art’ book included few female artists, hopefully that’s changed now. Things are changing for women and people of colour and that’s good for each and every one of us in the world.

Happened on your post just when I was re-reading the Song of Hiawatha for the first time in years. The rich language and imagery suggested many paintings. And Edmonia Lewis actually acted on that impulse! I particularly liked Ch XIV “Picture-Writing”.

Thank you for sharing this piece on Edmonia. I have read about her before but your refresher gave me more insight.

On exhibit in New York City! Forever Free, by Edmonia Lewis, 1st American sculptor to celebrate the emancipation of women. [met.org/Visit] @MetMuseum-on loan from @HowardU.

https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2022/carpeaux-recast

One of my favourite sculpture books, American Women Sculptors: A History of Women Working in Three Dimensions (Rubenstein, 1990), begins in Revolutionary times and continues to the Vietnam Memorial in Washington DC. Significantly, the book devotes an unusual 5 full pages to Lewis, and expands on some of the stories Jason related. One example is how she came to carve Wordsworth’s portrait. She “waylaid” him on the street, memorized his features, and roughed out a portrait of him from that. Much later, when he agreed to sit for a formal portrait by her, he was delighted to discover that she had already started it!

All anecdotes from her life aside, her sculpture stands now as among the best works this continent has produced. Given all that, it is no wonder Rubenstein introduced Lewis as “the first American sculptor of color to gain an international reputation…” She is one of my heroes.

Thanks, Jason, for this –so interesting! She was remarkable! I hope to see her work at the Met when I next get to NYC.

Also there is an interesting book, “The Story of Art–Without Men,” by Katie Hessel.

My 2nd daugther (or step daughter in some lingo) gave it to me–and said, “Someday you’ll be in it!” Made me happy to receive the book and the sentiment!

Thank you Jason for bringing her to my attention- I’ve never heard of her and/or seen her work.