“Art is harmony. Harmony is the analogy of contrary and of similar elements of tone, of color and of line, conditioned by the dominate key, and under the influence of a particular light, in gay, calm, or sad combinations.”

— Georges Seurat

Overview

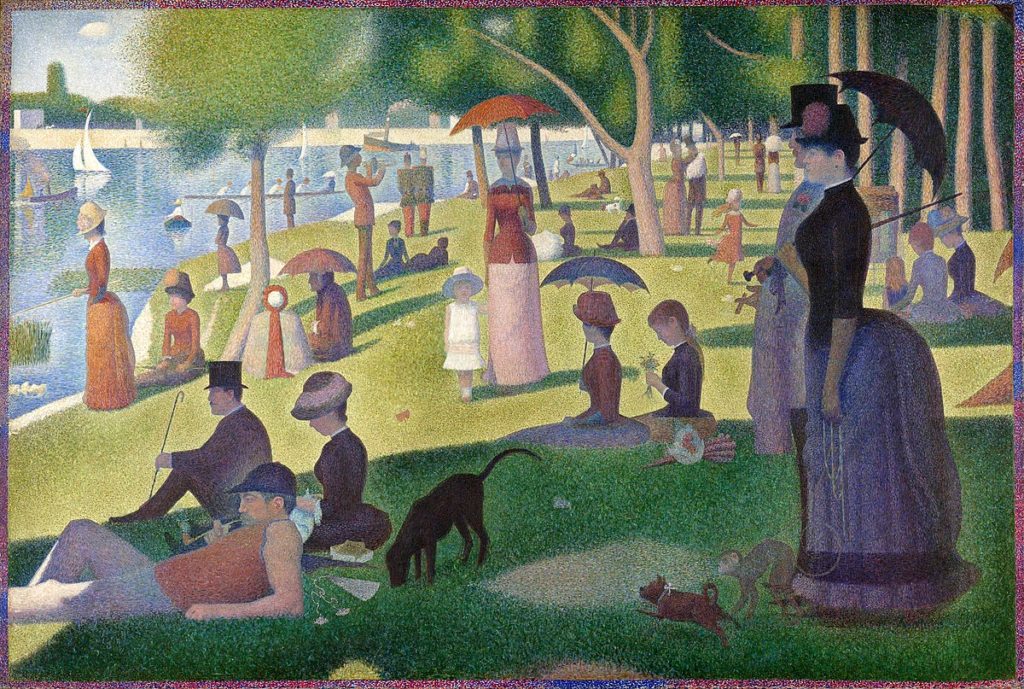

A Sunday Afternoon, with its tiny dots of adjacent colors and its stiff, distinguished figures, was an important turning point for post-impressionism and remains famous and influential, and for good reason.

On its own, the piece is interesting, but to really appreciate it, it’s helpful to also look at Bathers at Asnières, the piece Seurat painted just before it.

Background

Seurat painted Bathers at Asnières in 1884. It was a large piece, measuring 79 × 118 inches, depicting a group of working-class people on a bank of the Seine.

After completing it, Seurat submitted the painting to the jury of the Salon, hoping to have it exhibited there, but it was rejected. Many of the artist’s contemporaries weren’t quite sure what to make of it.

Despite the criticism the piece received, Seurat began work on A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, which would be even larger and more experimental than Bathers. Seurat’s most famous painting wouldn’t be finished until 1886, following two years of numerous studies and meticulous work.

He exhibited his masterpiece at the final exhibition of the Impressionists the spring he completed it, kicking off the Neo-Impressionist movement.

Bathers at Asnières

If you put A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte side by side with Bathers at Asnières, you’ll notice that they seem to mirror each other, and that’s because the working-class bathers are positioned across the river from the more bourgeois crowd on the Island of La Grande Jatte.

Together, the two pieces seem to make an interesting statement about class. While the working-class bathers are bathed in light, the more posh people on the Island of La Grande Jatte are largely in shadow. And behind the stately appearance of those figures, there are subtle clues that there may be corruption in their ranks, like the leashed monkey and the fishing rod, which have been interpreted as symbols of promiscuity, especially because the island was known at the time as a place where the wealthy could find prostitutes.

The allusions to the failures of the upper class may or may not have been intentional, but just the fact that Seurat chose to paint labourers the way he did, especially on such a large scale, was unique for the time period, when rapid urban development had greatly expanded the population of lower-class individuals in Paris. Interesting, Monet painted the same area about a decade earlier, but his piece had a significantly darker mood.

While this connection to the previous painting suggests that Seurat may have been making a statement about class, another major source of inspiration for the piece was the Parthenon frieze, as the artist told critic Gustave Kahn. You can definitely see similarities between the ancient Athenians and the stiff profiles of Seurat’s figures.

Seurat’s Life

Georges-Pierre Seurat was born in Paris in 1859 to a former legal officer from Champagne and his Parisian wife.

Georges-Pierre Seurat was born in Paris in 1859 to a former legal officer from Champagne and his Parisian wife.

Seurat first studied art at the Municipal School of Sculpture and Drawing (French: École Municipale de Sculpture et Dessin) near his family’s home and later attended the École des Beaux-Arts (pron. ay-coal day boze ahr), which was soon cut short as Seurat left for a year of military service.

When he returned to Paris, rather than continuing his formal education, Seurat rented an apartment for himself and began sharing a studio with Edmond Aman-Jean. He spent two years mastering monochrome drawing techniques, and the first piece he displayed at the Salon was a drawing of Aman-Jean.

Though he had left the academy, Seurat continued to study the work of artists he admired and to study color theory with intensity, which eventually led him to embrace pointillism.

Later in his career, Seurat would become enchanted by Madeleine Knobloch, the model depicted in his painting Young Woman Powdering Herself. Seurat kept their relationship a secret, even as Knobloch moved into his seventh-floor studio with him in 1889, just a few years after he painted A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. Soon she became pregnant and gave birth to a son, Pierre-Georges.

Tragically, Seurat died of an unknown illness in 1891, leaving his last piece, The Circus, incomplete, and his son died of the same illness just two weeks later.

It’s amazing that an artist with such a short life, living only to 31, could have such a lasting impact on art history.

Conclusion

A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte is one of the most famous and influential paintings of the post-impressionism era. Painted by Georges Seurat, the piece is interesting on its own, but is made even more so by its connection to Seurat’s earlier painting, Bathers at Asnières. Together, the two pieces make an interesting statement about class. Seurat’s use of color and light in the painting is also quite unique and influential.

How do you feel about Seurat’s masterpiece?

Are you a fan of Seurat’s style and his painting “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte?” Have you seen Seurat’s work in person? How do you feel about art as social commentary? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

I’ve seen his work at the Art Institute of Chicago…it’s amazing in person! I didn’t know that he only lived till 31!! WOW! Interesting article as I really don’t know that much about him.

I’ve seen this piece at the Art Institute also, the size just blew me away. I’ve seen the picture in books and noted the dimension, but until I entered that gallery the huge size just never clicked, I was awestruck…this was 40+ years ago so I’m not sure it’s still in Chicago……

Agreed – the impact is amazing

It’s still there!

You can’t seem to talk about pointillism without mentioning Seurat, but while his paint-handling technique is commendable, I find his rendering of the figures (even Bathers) rather stiff, and the composition feels like an untrained tourist/amateur photographer.

And I’ve heard the “two years” figure for Grand Jatte, but now I’m wondering how much of that was the piddlyness of the technique itself (I know pointillism is one of the slowest methods to get paint onto a canvas), and how much was the research of developing it.

I love the effect – I see the figure and composition as highly stylized in a revolutionary (for the time) way.

Thank you for this post.

It is a wonderful moment in art history and worth the time contemplating the possible influence of class division and importantly the revolutionary scientific revelations of the impressionist and early modern period. Seurat’s process of optical color juxtaposition can still be seen in contemporary impressionist work as “broken color” applications. As artists, the contemplation of the present culture wars and conversations about a civil democratic society are rich content for inspiration. However, many artists intent on marketing their work seem to prefer to walk that razor edge between political and religious division or avoid such subjects all together, rather than risk alienating their collectors. More food for thought.

Where are these painting now? It would be great to see them in person.

Sunday Afternoon is at the Art Institute Chicago and Bathers at Asnieres is housed in the National Gallery, London.

Art as social commentary is important and I suppose Jean-Michel Basquiat represents this in an intensely emotional impact of color and subject matter. Not the subtle precision Seurat for damn sure, but todays world is not subtle but in your face just as Basquiat was. Hard to believe he has been gone for over 40 years yet his paintings still astound me. The art of the street and not the beach. “Irony of Negro Policemen’

As a scientist, this painting has always blown me away for two reasons.

One is that Seurat developed the theory that led to pointillism in discussion with scientists who were developing theories about colour vision. (Their collaboration is rumoured to have been lubricated by absinthe.) The other reason is that I understand he painted this enormous work in an attic that did not allow him to stand back far enough to see the colours fuse, as predicted by his theory. He was so close to the forest as he worked that all he could see was the trees (dot). If that’s true, it’s amazing.

As a sculptor it blows me away beause Michelangelo exercized something similar to Seurat’s theory in leaving most of his sculptures not smooth, but incised with parallel grooves from a toothed chisel. Close up, those grooves are rendered into parallel bands of light and dark whose intensity varies with the angle of the light. Viewed at the distance at which he intended them to be seen, the grooves or the bands of intensity fuse into smooth curvature, and the result is a perception of perfect smoothness. I don’t think they had absinthe back in Michelangelo’s day.

Terrific insights Lee – thanks for sharing!

Lee Gass and Jason Horejs, Thank you both for such an educational journey into two fascinating artists. Just this morning an artist friend told of her experience seeing Seurat at the Chicago Institute. She could not believe the effect of standing up close, seeing the dots, then backing away to observe the whole painting. Until you wrote this, Lee Gass, I did not know that Michelangelo used a grooved chisel in his sculptures, thank you!

Thank you Jason for taking us out of the ordinary and bringing us into the extraordinary

I also have seen his work in the Institute in Chicago. I thank you for that bit of history of him. I tend to be open minded about art and artist. They share their gift with us, so I do not make any judgement I enjoy what they give some much more than others I am awe stricken by what comes out of the minds of some.

Stunning works. I love the connection you traced between the two pieces. Seurat (and Signac) is hugely influential in my work although I tend more towards Pointillism than Divisionism. I do not see this style/technique of work celebrated enough in contemporary galleries or exhibits. More often than not, I find myself in a position of explaining to viewers exactly what they are looking as far as execution.

I have not see this work in person, although in 2001 I was fortunate to see the originals of Alessandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and Primavera in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. Two of my all time fav paintings. I still marvel at the memory of his brush strokes on them, Venus being my favorite. I think it’s because I connect it with Heinlein’s To Sail Beyond The Sunset Book cover. I just signed on to your blog and am enjoying it. A lifelong artist, I now want to share my paintings and illustrations with the world. Ciao bella, Lauri Jon

When I first experienced Seurat’s Afternoon at the Park in Chicago I was overwhelmed. An the staging had a lot to do with it. It was hung in a large galley on the wall that you come into the galley, so you don’t see it right away. As you walk into the room your natural inclination is to turn to your right. I really didn’t notice the painting at all until I was a quarter into the gallery and turned to my left. BAM it hits you. Now this is a very large painting. Now this painting is over 6 ft tall an almost 10 feet wide and the vision of it hits like a ton of bricks. It’s powerful. So powerful my eye’s started to well up and I was dumb stuck at my emotional reaction to the painting. WOW!!! I later learned that this effect is called Stendhal Syndrome (look it up). I’m not going to say it was a religious experience, but that’s how I imagine one would feel like. It was a one of a kind experience from over 30 years ago I will never forget.

Stendhal Syndrome

Great analysis of putting these two paintings together. I have seen them both in the flesh and they are fantastic.

I cry tears of joy when I see this in Chicago. Many beautiful paintings there. But nothing compares. I spent most of my time last visit studying this painting. Best of museum. Totally awesome.

I thought that I viewed this at Moma years back,very impressive,,

when it was on loan of course,

I always enjoyed Seurat work, very innovated for that time..

I have seen this work many times during my early years. The immense size and perspective give the feeling you could just walk into the painting. However the style gives a stiffness to the figures that just doesn’t appeal to me.

I have seen it. I wasn’t particularly a fan of his until I saw this peice – larger than life! I think on the card beside the painting, it stated that it took Seurat four years to paint it! It was an incredible experience, seeing the painting. It hits you practically as you walk in!. I remember getting up close and standing back, numberous times. At one point I realized that I had only ever seen it in books and I started to get emotional. Here I am, now sitting on a bench positioned in front of the painting and starting to cry. I felt embarassed as I did so. Near me was a Japanese woman doing the same thing, then I didn’t feel so silly.

Whether you like the style or not, it certainly gives something to think about. It was a new way; one that took a long time to create. To me, it is ingenious that the yellow dots next to the blue dots made green. I mean, we all know that. But put together in that way! It was wonderful!