Arrangement in Grey and Black No.

1

In my first Moments in Art History video, I talked about American Gothic, one of the most iconic paintings in American history. Whistler’s Mother is another American icon, although it was painted overseas in London.

The piece especially gained popularity in the United States during the Great Depression, when it was featured on a postage stamp along with the words “In memory and in honor of the mothers of America.” Just a few years later, in 1838, an eight-foot-high statue based on the painting was erected as a tribute to mothers by the Ashland Boys’ Association in Ashland, Pennsylvania. Since then, the painting has appeared in too many advertisements, television shows, and films. It’s even been called the Victorian Mona Lisa.

But like many of the most famous works of art in history, it didn’t garner praise immediately, and when it did receive recognition, it wasn’t really the kind Whistler was looking for.

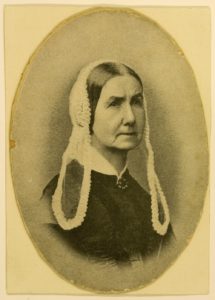

Whistler painted the piece while his mother was living with him on Cheyne Walk in Chelsea, London. Legend has it that Anna Whistler became the subject of the painting when Whistler’s intended model couldn’t make the appointment and that she sat for the painting because she couldn’t stand for a long period. Still, we don’t know Whistler’s original intent for the piece.

Whatever the case, the painting was displayed in the 104th Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Art in London in 1872 after nearly being rejected. Whistler already had a shaky relationship with the British art world, and the criticism the piece received only increased his frustration. As a result, it was the last piece he ever submitted to the Academy.

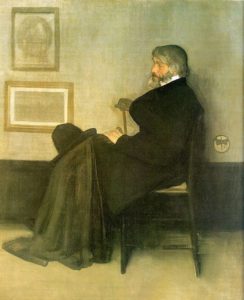

Whistler had titled the piece Arrangement in Grey and Black. Still, the academy added the subtitle Portrait of the Painter’s Mother, apparently unimpressed by Whistler’s attempt to present a portrait as something other than a portrait. From this subtitle, the painting got the nickname Whistler’s Mother.

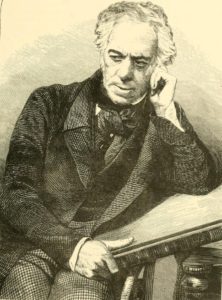

After viewing the piece, British historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle sat for a similar painting, which would be titled Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 2.

The painting of the artist’s mother began to attract favorable attention when it was acquired by the French government and shown in Paris’s Musée du Luxembourg.

Of course, Whistler was thrilled with the painting’s new home, seeing it as a “slap in the face” to the London art scene that had disrespected the piece.

As a major proponent of “art for art’s sake,” Whistler likely would have been less thrilled had he known that the piece would become so famous for its maternal subject.

Confused by the public’s insistence on calling his painting a portrait, Whistler wrote in his 1890 book The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, “Take the picture of my mother, exhibited at the Royal Academy as an ‘Arrangement in Grey and Black.’ Now that is what it is. To me, it is interesting as a picture of my mother, but what can or ought the public do to care about the identity of the portrait?”

As it turns out, we care a lot, and as a result, the piece has become one of the most famous works by an American artist outside the United States. It has been exhibited several times in the United States, spending time in the National Gallery of Art, the Detroit Institute of Arts, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and several other American art museums. The piece is currently back in France at the Musée d’Orsay.

The Artist’s Life

James McNeill Whistler was born to Anna McNeill Whistler and railroad engineer George Washington Whistler in Lowell, Massachusetts. However, he would later claim St. Petersburg, Russia, as his birthplace, saying, “I shall be born when and where I want, and I do not choose to be born in Lowell.”

The family did move to St. Petersburg when Whistler was a child. His father had been offered a position by Nicholas I of Russia to work on the St. Petersburg-Moscow railroad.

Whistler was a moody child, but his parents found that drawing calmed him and allowed him to focus. He began taking art lessons early and enrolled at the Imperial Academy of Arts

when he was only eleven.

The young artist followed the traditional curriculum of drawing from plaster casts and occasional live models and reveled in the atmosphere and art talk with older peers. A few years later, he met well-known Scottish historical painter Sir William Allan, who told Whistler’s mother, “Your little boy has uncommon genius, but do not urge him beyond his inclination.”

This advice turned out to be pretty prophetic. After Whistler’s father died of Cholera, the family returned to the United States, where Anna Whistler sent her son first to Christ Church Hall School in the hope that he would become a minister and then to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Neither went

very well. At West Point, Whistler constantly defied authority, spouted sarcastic comments, and earned poor grades.

He claimed to have finally been dismissed for a spectacular failure on a chemistry exam where he was asked to describe silicon and began by saying, “Silicon is a gas.” As he himself put it later, “If silicon were a gas, I would have been a general one day.”

However, during his studies there, he did have the chance to study drawing and mapmaking with Robert W. Weir, which came in handy after Whistler’s dismissal from West Point when he took a job as a draftsman. He found the job boring, leading him to pursue fine art seriously.

As you might have guessed, based on what happened with Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, Whistler’s West Point misadventures were not the end of his attitude problems. After a permanent move to Europe and time studying in France, he settled in London, where he spent almost as much time making enemies as he did painting, butting heads not only with the Royal Academy but also with several prominent English figures, from Oscar Wilde to John Ruskin.

He also struggled financially and had a string of mistresses before marrying Beatrice Godwin in 1888. She eventually became ill and succumbed to cancer, and Whistler himself died at 69 in 1903.

Other Great Whistler Works

Along with Whistler’s Mother, some other famous works the artist produced include Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl, and Nocturne in Black and Gold. The artist often used musical terms to title his work, finding a connection between the visual harmony he created and the sonic harmony in music.

Legacy

James McNeill Whistler was a controversial and complex figure, but there is no denying his talent as an artist. His most famous work, Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, better known as Whistler’s Mother, has become an icon of American art, and its story is as interesting as the painting itself. Whether you love or hate his work, there is no denying that Whistler was a master of his craft, and his legacy continues to live on through his art.

What do you think of James McNeill Whistler’s work? Do you have a favorite painting by Whistler? What do you think of his Mother’s portrait? Do an artist’s intentions for a creation matter? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

What a great article.

He subscribed to the “Art for art’s sake” idea.

It took me the rest of my life to grasp what Whistler meant to me.

“Arrangement in Black and Grey” directly addresses what painting is.

So many of us still don’t get it, or if we feel we do, it is a self-evident non-starter.

He was deep into the reality that “art” represents itself first. To be an artist in the vein of Whistler is to recognize what and how the making of art is.

His titles only point this out. I keep coming back to “Nocturne in Blue and Silver- Cremorne lights”.

I have come to the point where his method of titling fits with my intentions.

Often I am put off by works with “Untitled” as the title. I want to know, by way of the title, the where, who, what, when of the piece on one hand, but I understand the difficulty of putting a meaningful title on many of my own paintings. i am aware that art has meaning for the creator that may be very private or intentionally obscure to the viewer. Your article is a good reminder that we cannot always know nor should we require knowledge of the artist intent or meaning for a piece. The experience of the art is what the viewer brings to the piece as well as what the artist brings.

Intentionality is a sticky wicket in any case, because what an actor “intend” by an action is completely transparent to us; we make it up, based on whatever evidence is available to us and how open we are to consider it. Soviet intentions in insisting public art glorify the state, the state’s actions or leaders. Portraiture of the Renaissance and later seems to have been as much or more about how subjects wished to be seen, as what they looked like.

I worked on a sculpture for a year before I discovered, in a deep dive into a corner of Jung’s psychology, what my intentions had been in carving it. Suddenly, I knew what I had been doing for a year of work on the piece (I was a part time sculptor back then). Anima 1 is the sculpture. Others have been similar, in science and education as well as art. Often, I don’t know what I am doing when I start. Life for me seems to be a process of unending discovery, partly because I keep trying things I don’t know how to do. When I create plans, when they work, creation happens suddenly when I reealize (when it becomes real for me) what I’ve already been doing.

As much as I can, when I look at a piece of art or a person, I try not to guess the intentions of their actions and pay close attention to what they actually do or say. Sometimes I surprise myself to discover things I find beautiful. How else could it be?

Of course the artist’s intentions matter – but not to everyone. They matter to the artist, and to art history, and possibly to somewhat sophisticated viewers, to people tho care deeply about the art & artist at the time to work is presented. But any piece of artwork is on its own when it hits the public. It will live if & as the public sees fit, basically. Society relates to things on the whole in the simplest way – a mother is supposed to induce universal feelings of goodness, so the work will be promoted that way by the people working to find viewers and buyers. Simple as that. I spend a fair amount of time wondering what viewers might see in my non-objective work, and when I’m told I’m usually surprised! Artists, stick together and sigh together, but let your art have its own life, while you share your intentions with receptive people, too. Make it an AND game, expanding ways to appreciate & enjoy.

Well written!

Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1 plays with our perception of the light and space depicted. The brightest object is the painting, as though lit by intense diffuse light from a window behind the artist. This and the highlights of the curtain ornaments and the mother’s bonnet distract us from what should be the point of focus, Anna Whistler herself. Also, the small pedestal Anna’s feet sit on appears to be well behind the line formed by the legs of the chair — a clear distortion of space. I take these cues as Whistler’s subversion of our traditional way of viewing a portrait on a path to a new way of understanding two-dimensional images.

My favorite Whistler work is a painting and a room: The Peacock Room which can be found at the Freer Gallery in Washington DC. (https://www.si.edu/object/harmony-blue-and-gold-peacock-room%3Afsg_F1904.61) Whistler designed this room for the Leyland family in London and the centerpiece was his painting “Rose and Silver: The Princess from the Land of Porcelain”. When I first discovered this little gem, in the early 1980’s, the porcelain was gone but the painting was still there and the room and painting transported me to another time and place. Sadly the painting has been removed (last time I was there anyway) and the room isn’t the same without it.

I have overheard viewers at my showing professing to understand what I intended or was thinking of. I use to have trouble with that or was annoyed by their conjectures. Now I leave them to their imaginings. My wish is that they find something for themselves instead of worrying about my state of mind.

Ahh, well said and I agree with you. I find my best pieces are those with a purpose from the beginning. However, when someone sees or feels something else when looking at my abstract so be it and I encourage it. At least there is a connection, their connection based on my artistic stimulous.

While I seek to evoke endearing emotions in my work, it’s enough for me if people enjoy and draw meaning based on their own unique experiences. I am fascinated by birds. I have a fan who loves my work, but hates birds. I still don’t know what she sees in her head when looking at my work.

So bottom line: It only matters to whom it matters.

Great article, Whistler did indeed butt heads with many, John Ruskin for sure. His relationship with Oscar Wilde was a bit different. I don’t know if they were really friends, but the story goes that they would drink together in private and hurl insults at each other in public, across crowded dining rooms etc. this got both of their names in the gossip columns or the society columns of the times. Free advertising!

This post is fascinating and the comments were highly enjoyable. Not a huge fan of Whistler’s art, but the title “Arrangement in Black and Grey” makes the work more interesting, imo. I took a great deal more time observing the piece. Black and grey tonal artwork with the freshness of white and ivory is particularly elegant; and I really love that. Probably, the idea that Whistler would present his mother in such a sad attitude did not appeal to me. Thank you, Jason.

Does the painting title matters ?

Frequently, but not always.

Some titles will make you look more closely at the work to discover “Why that particular title?” While I was researching prices, I came across “Bear in the Woods”. I had to really look at that woods to find the bear which was anything but the focal point since it was hidden in the shadows down near a corner of the painting. On the way, I developed quite an appreciation for the artist’s rendering of different trees.

One mentioned here that learning the actual title of “Arrangement in Black and Grey” made him radically shift how he viewed the painting.

So, yes, titles frequently matter.

Thank you Jason, interestingly I just used that painting in one of my paintings “Aging Gracefully” https://www.fleurspolidor.com/swim-suit-series#/aging-gracefully/ just to show how different women are today. A lot more active than how Whistler represented his mother.

I am also a published poet, as well as an artist. Titles, therefore, are really significant for me, and play a role in the identity of the whole piece. My collectors usually appreciate this, and share my enthusiasm for finding the right words. Some of my colleagues even ask me to help title their work. However, all artists are not alike. I find those who are deliberately vague or literal (like this example) to be rather lazy, actually. That may seem overly critical or superior, on my part; but I balance that judgement by also acknowledging that all artists deserve their own voice. That’s what makes them an artist.

I create a painting for others to view – not myself. I do not have single one of my own paintings in my house. Whatever my intent or motivation was, is meaningless to anyone but myself. The viewer will impose his/her own feeling/meaning on the piece. As long as their check clears the bank – I don’t care.

I admire Whistler for his atmospheric paintings later in life. He was out on a limb, taking his art where no other artists dared tread. This article, however, taught me much about Whistler’s life and philosophy. I’ve mostly read about him in the context of the Pre-Raphelites and Ruskin. I never even knew he was American! Thank you!

The marine nocturnes at the Freer Art Gallery in Washington DC are some of my favorite paintings of his.

The artist James Whistler is unfortunately at times misunderstood by today’s audience.. Considered by many critics, and historians as the first great American painter, his work could be considered revolutionary for the time in which he painted. He was an artist who was very involved with abstracting things down from pictorial realism into shapes, while at the same time still holding on to minimally modeling form. He had the keen ability to distill his subject down with just enough information to convey what he wanted to say. As his work progressed, it became more and more abstracted. Throughout all of his work there is a consistent preoccupation with the push and pull of the positive and negative space, which is clearly evident in his painting highlighted here. Most people assume it is simply a portrait of the artist’s mother, however in reality his primary focus was actually the relationship of shapes, and tones, in an almost lyrical sense. His mother simply served as the armature for his concept. It is a difficult painting for some people to connect with due to the stoic nature of the model, and the lack of narrative.

Whistler was an artist who was brave, and enjoyed pushing himself, regardless of brutal critics of his day. Another example of this which is hard for us to image today, is his painting: “Symphony In White” (also at times referred to as “The Girl In White”). What seems like a pretty straightforward painting today, created quite a stir in its day. Perhaps the greatest compliment he could receive was that upon its completion every artist was painting their version of a girl in a white dress. The progressive history of art, has somewhat left much of Whistler’s work overshadowed by other artists who built upon the artist’s genius. It is easy to understand that the more one looks at his work, the more that the viewer discovers.

This was one of the best descriptions of Arrangement in Grey and Black.

I am so happy you did not emphasize the mother but the more important elements in the painting. For this I thank you Ray.

(btw, it was immensely nice visiting your gallery and meeting you in person late last July)

Do the artist’s intentions matter? They most certainly do. It guides the painting design, process and the final production. One of my college professors put the nature of artistic intention and public reception rather succinctly when he said, “When art leaves the studio, it gets a life of its own. You have no control.”

Thank you Jason for another interesting article. My favorite Whistler painting is the watercolor sketch “Mother and child on a couch” https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1069245/mother-and-child-on-a-watercolour-whistler/

True to one of your earlier articles, I do believe titles are important and share the sentiment that “Untitled #4” etc seems lazy and detached.

However, at a recent art exhibition we collaborated with a local poetry group. The poets were invited to write poems based on the art on show. One of the poets who is an artist herself brought her work in without titles and did not wish to have them “labeled”. She explained that when she looks at a painting she wants it to speak to her personally, But when the title contradicts her initial response to the image, she finds it impossible to “unsee” the given title!

I was at the Musee D’Orsay and, due to time constraints, I was picking and choosing which rooms to explore. I walked by a room and my husband called me back to say he thought I may want to see it. I almost breezed by Arrangement in Grey and Black and that would have been a tragedy! Such a powerful work!

I love Whistler’s work. The abstract ideals of composition and his explorations and understanding of color underpin each work. An artist grounded in these can spend a lot of time meditating on his paintings. His work is delicious.

I really liked reading about Whistler. I enjoyed the comments even more. I name my pieces, but can’t remember their names when asked a few years later. lol. Doesn’t matter though; most collectors retitle the art to their liking.

Oh, this is a great article. And yes, artist intentions matter and they reflect in the title he/she chooses. The artist’s intentions play a big role in creativity process; however, the buyer connects to the art with his/her own intensions/experiences and finally that’s what matters and stays with the piece. My humble opinion.

A very interesting discussion. Talented yet hard headed seems to be a trait shared by many artists.

The Whistler House Museum in Lowell Massachusetts houses many of Whistler’s paintings and etchings. If you are ever in Lowell find time to visit it. You will be pleasantly surprised at the artwork the museum has acquired. I was pleasantly surprised with his etchings and a copy of Whistler’s Mother.

Thanks, Jason, for sharing on Whistler.