I know the feeling. You have spent months, maybe years, creating a body of work that feels deeply personal. You have researched a gallery that seems like a perfect fit. You have drafted the email, attached your portfolio, and now your finger is hovering over the “send” button.

Your heart rate speeds up. Your palms get sweaty. You feel a distinct sense of smallness.

Why is this moment so terrifying for so many artists?

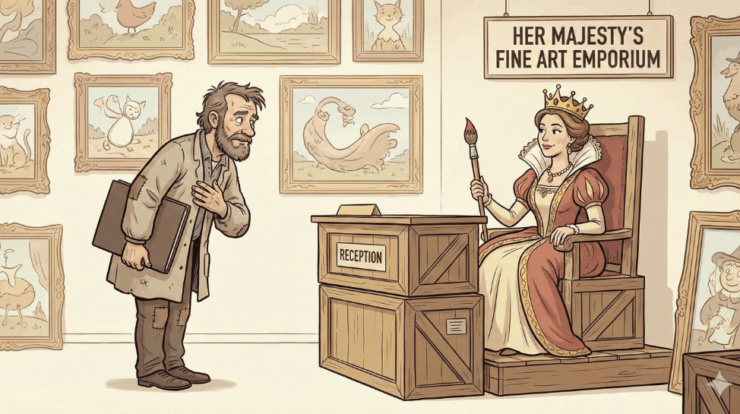

Recently, an artist shared with me that despite knowing better intellectually, they still emotionally view gallery owners as wielding immense “power and authority.” Approaching them feels intimidating because the artist feels like a petitioner begging for entry at the gate, while the gallery owner holds the keys to validation and success.

This is perhaps the single greatest psychological barrier artists face in their careers. It is also based on a fundamental misunderstanding of the art business relationship.

If you want to succeed in getting representation, you have to dismantle the myth of the “almighty gatekeeper” and realize that you are entering a partnership of equals.

The Illusion of the Power Imbalance

It is easy to see where the feeling of inferiority comes from. There are millions of artists making work, and a finite amount of professional gallery wall space. When you look at the math, it feels like it’s a buyer’s market and the galleries hold all the cards.

When you feel like one of thousands clamoring for attention, you naturally adopt a posture of subservience. You feel lucky just to be noticed. You worry that your work isn’t good enough, that you aren’t good enough, and that a rejection from a gallery is a definitive judgment on your worth as a human being.

This mindset is paralytic. It stops artists from reaching out, and when they do reach out, it makes them sound desperate rather than professional.

The Reality: It’s Just Business

Let’s strip away the romance and the intimidation of the “white cube” art space.

A commercial art gallery is a retail business. Like a shoe store needs shoes on the shelves to survive, a gallery needs art on the walls to survive. If I don’t have exciting, high-quality inventory that my clients want to buy, I go out of business.

When you approach a gallery for representation, you are generally proposing a consignment relationship. The industry standard is often a 50/50 split.

Think about what that split means. It means you provide the product (which took years of training and labor to create), and the gallery provides the venue, the marketing, and the sales staff. When a sale occurs, you share the revenue equally.

That is the definition of a partnership. You are not asking for a favor; you are offering a business opportunity. You have something of immense value—your art—and you are looking for a partner competent enough to sell it.

The Secret Insecurity of Dealers

If it helps to knock gallery owners off the pedestal you’ve placed them on, here is a secret from the other side of the desk: We feel the exact same way you do.

I might seem intimidating to an unrepresented artist, but when a major, high-net-worth collector walks into my gallery—someone who could buy out my entire inventory with pocket change—I feel that same imbalance of power. I worry my inventory isn’t good enough. I worry I’m not sophisticated enough. I feel like they hold all the cards.

We are all just human beings trying to run small, often fragile businesses. Gallery owners aren’t omnipotent arbiters of taste; we are merchants looking for reliable partners.

How to Shift the Dynamic

How do you move from intellectually understanding this to emotionally feeling it? How do you stop your hand from shaking when you hit send?

1. Utilize the Law of Large Numbers If there is only one gallery in the world you want to be in, that gallery holds immense power over you. If they say “no,” your dreams are crushed.

But if you have researched a list of 100 qualified galleries that fit your style, no single gallery holds the keys to your success. A “no” from gallery #3 is irrelevant because you still have 97 more to go. By expanding your prospects, you diffuse the power of any single gatekeeper.

2. Lead with Professionalism When you approach a gallery with confidence and organized materials, you signal that you are a business professional ready for a partnership.

When you act like a pro, you begin to feel like a pro. This means having your portfolio polished and easy to review. As I discussed in my previous article, “The Psychology of Yes,” presenting your work clearly and cleanly removes friction for the dealer. It shows you respect their time and take your own business seriously, which instantly levels the playing field.

Walk in Tall

The next time you prepare a submission, take a deep breath and straighten your spine. You have talent, you have inventory, and you have drive. You are looking for a business partner who deserves to represent you, not a savior to validate your existence.

What’s your experience?

Have you ever felt intimidated by a gallery owner, only to later realize they were just a regular business person struggling with their own challenges? How do you psyche yourself up before sending out portfolios? Share your stories in the comments below.

Thank you! I just went through this exact scenario this morning. Actually, my first ever submission. I thank you for giving me the tools. Hopefully I will get a positive reaction!

“Walk in Tall … You are looking for a business partner who deserves to represent you,”

This isn’t how I was raised but now that you mention it, I’ve done this “tall thing” before, I thought, until today, that these instances were just flukes of exuberance. Now I’m thinking there has always been something there lurking under practiced humility.

Let’s face it. Do you believe in your ideas and your acquired skills?

As i was fond of saying to my young students, “Where is your spirit of adventure? What’s the worst that could happen. The Big Gradebook in the Sky is closed today.”

Little did I know I would have to live that snide remark, but here I am.

Ready to see what happens.

I was an advertising sales executive for a large daily newspaper and a predominate network television station, yet when I try (or even think about) approaching a gallery I become completely overwhelmed by insecurity and doubt my own work’s value. I guess perhaps because it is so personal . . and I lack a lot of art education, having started after I retired, but they have been well received and I’ve sold quite a few on my own.

Your suggestions are sound and just reading them I felt somehow taller and straighter!

When you have created art for 50 years for a living and have more connections than most galleries the dynamic switches to the other side. The gallery owners become the nervous ones too eager to please or want to plunder your connections to clients that they have not worked with before. it is more common in my case to turn down galleries than it is to work with them.

. i find that much harder to deal with than the early carrear jitters of the first few gallery submissions, interviews etc. The relationship is both business and personal. if its not a good match walk away, there will be another opportunity around the corner.

sometimes it is difficult to find a partener in life the gallery artist relationship is no different.

This is a helpful perspective! I look forward to this phase of my art career!

I’ve been sending out submissions again this year, and just sent one yesterday to one that I would love to partner with. I sent what I thought was a strong portfolio and statement. Of course I have not heard back yet, and as I watched my mood get slightly insecure this morning, I realized, hey, stop it! Even if they never write me back, I sent a good proposal to them, in a professional manner. I can be feel good about that, and know that it is NOT fame or fortune that defines my worth as a person or the success of my art career. I can still and always make art, which makes me happy. In a strange way, if they don’t want to work with me, it’s not necessarily a reflection on me or my work. It’s just not the right time or situation. Meanwhile, I still get to choose to be happy.

Great perspective!

It’s finding that list of 100 qualified galleries. I’ve been researching and finding so many don’t put pricing on their site so you can see if you’d be a good fit. And many specifically state they don’t accept submissions online or in person. How can they stay in business? When it feels like so many have closed the door in your face online before you even have an opportunity to reach out to them, it can add to your feeling of inferiority (like I’m not part of that elite group and they don’t want me to be). But I press on. Thanks for the point of view.

I guess not all gallery owners consider themselves equal partners with their product suppliers (artists).

And my experience with the gallery business owners has been less than joyful. The contractual restrictions on to who and where the artist can sell and exhibit seems stifling. And as much success as I’ve enjoyed on my own appears to mean nothing, perhaps even intimidating to some gallery czars. Which begs the question; why do so many retailers of art make it so difficult with … snooty attitude, complicated contractual restrictions, grudging commission payments, and poor communication?

Alright then, just for grins, what does the artist’s work look like? Maybe it is c**p and deserves disdain.

Perhaps it’s all in the eye of the beholder.

I have used your approach with a digital portfolio and researching the galleries ahead of time, to be sure I am a good match, with great success. I confess I did have the sweaty palms and fear of rejection we all suffer from, but I have been well-received. Even the galleries that were not able to add me to their artists were kind and some asked me to stay in touch with new work. I think the research makes all the difference. And having a professional resume and brochure of my work as well as the digital portfolio helped me ‘stand tall” knowing they need me as much as I need them!! Thanks for your excellent advice!!