Introduction

I have been in the gallery business since 1993. Though I now own Xanadu Gallery in Scottsdale and Pinetop, AZ, I started in the business on the ground floor. My first job was in the backroom, shipping artwork for a Western art gallery in Scottsdale. The gallery had a high sales volume, so I got a lot of experience packing, crating, and shipping art of every shape and size. I shipped paintings and sculptures large and small and learned what was important in making sure artwork arrived safely.

Over the years I certainly learned some lessons the hard way – not every piece arrived safely. Sometimes, despite my best efforts, artwork would be damaged by the delivery company, and sometimes, I would neglect a minor detail, resulting in a shipping disaster. Eventually I became quite adept at it, and even though I eventually moved into a sales position and ultimately opened my own gallery, I continued to sneak into the shipping room from time to time to keep in practice. To this day I will sometimes pack and ship a piece myself – there’s something satisfying about the physical act of shipping a piece of artwork.

Shipping is both science and art, and I would like to share with you some of the lessons and techniques I’ve learned over the years.

While shipping is almost second nature to me, I know that it poses a perplexing challenge for many artists and gallerists. I know this first hand: Some of the boxes I receive at the gallery are packed atrociously. From these boxes it is clear many artists either don’t know how to ship their work effectively or they know but don’t care very much. I hope I can make your life a little easier the next time you have to ship a painting.

While this post will focus on shipping two-dimensional art – paintings, prints, photographs – I hope to have a companion post on shipping sculpture in the next several months.

Disclaimer

While the advice I’m sharing with you comes from years of practice and experience, there are no guarantees in the arena of shipping fine art. Sometimes, despite your best efforts, artwork gets damaged in transit. I cannot guarantee every piece you ship using the techniques below will arrive safely, but this will help you better your odds.

Another important thing to remember is that each painting provides its own unique challenges. While these guidelines will work in most cases, occasionally you will have to adapt them to meet the needs of your individual situation.

My Goals when Shipping Art

When shipping artwork, before I begin I have three key goals in mind. I have listed them here in descending order of importance.

Safety

One of the worst imaginable calls in the art business is from a client who has received a piece of artwork damaged in transit. No matter how great a work of art is, no matter how well you have served your collector, if the artwork arrives damaged your customer is going to be upset. Later we’ll discuss how to mitigate your client’s frustration and turn the disaster into an opportunity to provide exceptional customer service, but it’s far better to avoid the damage in the first place.

In my experience, most damage can be avoided with careful planning and packing, and this should be goal #1 when you are shipping art.

Professionalism

I have often declared that artists and gallerists are as much in the performance art business as the visual art business. We want to convey to the collector that the work of art they just bought, or are considering buying, is a masterpiece. Everything we do in relationship to the physical work of art should reinforce this message. When handling the art, we should do so respectfully and almost reverentially. This applies to how the art is shipped as well. When the art arrives on your client’s doorstep, you want the packaging to look like it is worthy of the artwork within, not something that fell off the recycling truck.

Efficiency / Economy / Ecology

Finally, I don’t want my shipping expenses to eat so far into my profit margin that the sale becomes unprofitable. While safety and professionalism certainly come first, those concerns have to be balanced against your costs. Yes, you could charter a jet and hand-deliver the artwork to your client to make sure it arrives safely and professionally, but this approach would be neither economical nor efficient (probably not all that ecologically friendly either). Ultimately, I want to ship the artwork for the least cost, while still maintaining safety and professionalism. These factors can be balanced, and I am going to give you advice that will save you money.

We are also fortunate to live during a “green” revolution, when recycled materials and energy efficient transport is becoming more easily accessible. I try to use recycled materials wherever possible, and many transportation companies will allow you to buy carbon offsets for your shipments inexpensively. With a little careful planning you can minimize the environmental impact of your art shipping activity.

The Right Tools for the Job

My father-in-law is an attorney by day and an avid woodworker by night and weekend. He has an amazing woodshop where he crafts fine furniture. I stand in awe of the finely detailed and precise work he does in the shop. His success is equal parts skill, practice, talent, and creativity. He can envision a piece of furniture then engineer and execute a design that allows him to manifest the furniture precisely to his vision.

While his talent, skill, and creativity are vital to execute his work, none of it would be possible without the vast array of tools he has assembled over a lifetime of woodworking.

Fortunately shipping is far less exacting than fine furniture making, but the importance of having and using the right tools is analogous. Your shipping will be simpler and safer if you have the right tools.

For about $100 you can assemble a basic shipping toolkit. I have five favorite tools I use consistently when shipping. While there may be a few additional tools that will come in handy from time to time, these tools are a good place to start.

Don’t skimp on these tools. You may pay a little more to get high quality tools, but this investment will quickly pay off in increased productivity and professionalism. A good tool will last years; you’ll want to rid yourself of a poor one as quickly as possible. In other words, you’ll actually spend less in the long run by buying and maintaining good quality tools.

My Shipping Toolkit Contains the Following:

Knife (Box Cutter)

A high quality, heavy-duty box cutter with lots of blades is one of your most important, most used tools. Once you start shipping seriously, you are going to be cutting cardboard like crazy. If your knife isn’t sturdy and sharp, your cuts are going to be messy. A dull, or rickety knife will cause the cardboard to crumple and buckle rather than cut.

I change the razor blades in my knife after every five packages – more frequently if necessary. Blades are cheap, especially if you buy them in bulk.

Tape Gun

For my tape gun, I prefer one with a handle that holds 2” packing tape. Find one that provides a way to adjust the gun’s resistance, usually through a knob or screw on the tape roller. You’ll see why this is important later when I show you how to most effectively use the gun.

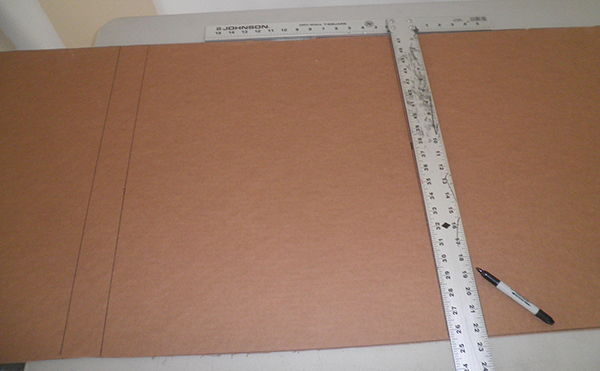

T-Square

A good T-Square will help you make straight, even cuts when modifying your boxes. The T-square is primarily used by builders who are installing drywall, which is typically 48” wide. I am going to recommend you buy your cardboard in 48” widths, which makes this the perfect tool for measuring your cuts.

Sharpie

Nothing beats a Sharpie for marking your cardboard for cutting. A pencil works as well, and some might argue that an errant pencil mark is easier to conceal or erase, but I like to get my score marks down quickly and boldly so there is no room for doubt. A marker line is hard to miss or confuse and is therefore ideal for marking up your packing materials.

I buy the versatile Sharpie markers by the dozens so I never have to worry about running short.

Box Sizer

All of the other tools in this list have been fairly common and are easy to find at your local hardware store. The last tool in my toolkit, the box sizer, is a tad more specialized and may need to be ordered online. But it is indispensable once you get the hang of using it. In essence, it is an adjustable tool that allows you to create even and smooth scores on cardboard. These scores then allow you to fold the cardboard wherever you need. With a box sizer you can modify boxes to fit your exact needs or even create boxes from raw cardboard. I actually use this tool far more frequently when packing sculpture, but it also often comes in handy when boxing up paintings.

Supplies

Just as having the right tools on hand makes it easier to pack your art professionally, having the right supplies on hand will simplify your shipping life and save you a lot of running around when you make a sale.

While packaging suppliers offer an overwhelming variety of supplies – boxes in every shape and size, tapes in every width, big bubbles, small bubbles, peanuts – you can meet most of your packing needs with just a small arsenal.

Again, the goal is to be able to do the most with the least.

Here are the supplies I try to have in my inventory at all times. While I occasionally have to special order a box for a particular work of art, nine times out of ten I can pack any two-dimensional artwork that comes my way using just these supplies:

Boxes

For my painting shipments I have three primary picture box sizes that I use.

28” x 4” x 24”

37” x 4 3/8” x 30”

36” x 6” x 42”

Your supplier’s sizes may vary slightly, but most will have boxes very close to these dimensions.

The two larger sizes are both telescoping boxes. Telescoping picture boxes are terrific because you can use just one if the artwork fits, or, if the work is larger than a single box, you can slide two boxes together to make a larger box. With a little surgery you can even slide four boxes together to accommodate still larger pieces.

The boxes are relatively inexpensive, and, when used properly, provide sufficient protection to keep your art safe in transit.

Palette Tape & Wrap (4” wide & 24” wide)

This versatile plastic wrap is perfect for giving your art a protective skin before boxing. It is very similar to the plastic wrap you use in the kitchen to cover casseroles and other food you want to keep fresh in the refrigerator. As the name implies, its main function is to wrap boxes on shipping palettes, but I will show you below how you can use the wrap as a protective coating around your art to protect against scratches and scuffs.

48” x 96” Cardboard Pads (single & double wall)

These are large, flat sheets of cardboard that can be used anytime you need extra padding or wrapping. You’ll see that I use these pads to provide an extra layer of cardboard between your art and the world, but you can also use them when you are customizing a box and end up with a gap, or when you need extra padding on a corner.

Bubble Wrap

Your kids (or grandkids (or you!)) love stomping on bubble wrap to create the satisfying little “pop.” It might be a little hard to believe that something that pops so easily has incredible power to protect your precious paintings. While any individual bubble is easy to pop, a sheet of the bubbles, working in concert, draws a surprising amount of strength by distributing pressure and impact across a wide area.

Bubble wrap both cushions the art and fills space, preventing unwanted movement within your packaging. When shipping paintings, bubble wrap should be your filler of choice – never use styrofoam peanuts when shipping paintings (more on this later).

I order two to four rolls at a time so that I always have plenty on hand. I do occasionally use the small bubble variety, but the vast majority of my shipments require me to use the larger, 1” bubble rolls.

I used to order both 36” and 24” wide rolls, but I found that I used far more of the 24” and, in the interest of space, decided to order only the 24” width, figuring that I can always use more sheets for those occasions when I need more width.

I also always order bubble wrap that is already perforated at 12” intervals. The perforations make measuring and cutting much easier and cleaner, and it costs the same as the non-perforated rolls.

We suspend the rolls on wires from the ceiling in our supply room so that the roll is out of the way and yet easy to access and unroll.

Packing Tape

I’m only going to say this once, but I’m going to say it emphatically:

Buy the very best packing tape you can afford!

I know we’re all on budgets, and we have to stretch to make those budgets meet our ever-increasing needs. While I understand that every penny counts, packing tape is not an area where you should be pinching those pennies.

I have received packages before where the art was literally falling out of the box because the tape had failed to hold. Cheap tape is harder to apply and harder to cut, and it doesn’t stick. You will end up having to use two to three times as much tape to secure your boxes, and even then you risk it not working effectively.

Cheap packing tape may actually end up costing you more, not to mention a client, especially if your artwork is damaged because the tape fails.

I always use 3.5 mil (that’s 3.5 thousandths of an inch) thick tape in 2” wide rolls. This will usually be the heaviest duty option available, but, when in doubt, ask your supplier what their best tape is, or just buy their most expensive option.

“Fragile” Stickers

I can’t remember where I heard it, but someone once said, “Plastering ‘fragile’ labels all over a package only ensures that the delivery company will toss the package under-hand instead of throwing it over-hand.”

This is probably true. I imagine that delivery company employees become pretty immune to those stickers after a while.

Even so, I use large fragile stickers on every shipment. The freight company might not pay much attention to them, but they make me feel better, and they let my clients know I care.

Packaging Procedures

Now that we have our tools and supplies together, we’re ready to begin boxing our first piece of art. Ideally, you would have a dedicated shipping area in your studio where you keep all of your supplies and tools and have a large table to work from. If this isn’t the case, clear the largest flat surface you can find – your dining room table is probably the next best candidate as it’s better to work at table height than on the floor.

Sizing

The first step in packing a painting is determining which boxes and materials you are going to use and then planning how to use them optimally. This process begins by measuring your artwork.

I start by determining which outer box I am going to use. My general rule of thumb is that I want to find a box that gives me a minimum clearance of about 2” all the way around the artwork.

As an illustration, let’s say we have an 18” x 18” painting that is 1.5” deep. We will therefore need an outer box that is at least 22” x 22” and about 5.5” thick.

In this instance, I would use my 28” x 4” x 24” box. This is a little bigger than we need, but because this package isn’t large enough to incur dimensional weight (see section on dimensional weight below) we are going to be charged by the weight of the box, not the size. So this box will work just fine.

You’ll notice that the box depth isn’t going to give me a full 2” clearance front and back, but I’ll have over an inch. If the piece isn’t extremely fragile, this is okay. Depth isn’t as big of an issue as height and width because the edges and corners are the most damage-prone areas of the artwork. We are also going to be double-boxing our artwork, which gives us an added layer of protection.

The ultimate goal of sizing is to give ourselves enough room to buffer the artwork from the outside world and to meet our freight company’s padding requirements. Most of the freight companies will only cover damage in packaging that gives you this 2” buffer. Be sure and read your freight company’s damage and packaging policy to confirm you are meeting their requirements.

Dimensional Weight

Another consideration when planning packaging is your freight company’s dimensional weight policy. If your delivery company always charged you shipping fees based purely on the weight of your package, calculating and minimizing your shipping costs would be pretty easy. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Because the size of a package impacts the number of packages a freight company can move just as much as the weight does, the companies have come up with a way to account for both dimensions by calculating the “dimensional weight” of a package. If a package exceeds a certain size threshold, the carrier will charge you based on the size or the actual weight, whichever is greater.

Though this sounds complicated, it’s really pretty easy to figure out. Simply contact your delivery company and ask them how they calculate dimensional weight and what their size thresholds are. Many of the companies will list this info on their websites. The formula typically looks something like this:

L x W x H / 166

and the company might say that any package that has a total volume over 5,184 cubic inches has to use the dimensional weight formula or the actual weight, whichever is greater.

This happens to be UPS’s current dimensional weight policy, which is why I’m using it here, but these formulas can change from time to time, so make sure you are using up-to-date information.

In our example then, we would first figure out the volume of our box. Since we are using a 28” x 4” x 24” box, we multiply those three dimensions to calculate our volume, which happens to measure out to 2,688 cubic inches. Since we are well under their 5,184 cubic inch threshold, we don’t have to worry about a big charge for dimensional weight.

When shipping larger artwork, you can often run head first into this issue. Let’s say we had a painting that required a bigger box. If we used our 37” x 4 3/8” x 30” box, we would find that our volume comes to 5,550 cubic inches. Since we’ve passed their threshold of 5,184 cubic inches, we have to factor in the dimensional weight (5,550/166), which comes to a total of 33 lbs. So, even if the painting only weighs 10 lbs, we’re going to be charged for 33 lbs since the size takes up so much space in their shipping van. Think of this extra charge as leasing van space.

Knowing this, if you find that the box has a lot of empty space inside, it might make sense to use a smaller box or to cut it down with the box sizer so that we avoid the dimensional weight charge. In this case if we took just 3” of the length or height of the box, we would be at 5,100 cubic inches and would only be charged for our actual weight.

It still might not be worth the hassle to cut the box down or get another box, but at the very least you should be aware of the impact that size has on your shipping costs.

Size Restrictions

You should also be aware that many of the common carriers, including UPS, FedEx, and the US Postal Service have unique size restrictions. Check with them to find out what those restrictions are. Exceeding these size restrictions will cause you to incur additional fees or force you to seek out another delivery option.

The size of the artwork dictates the size of the final package, and there are going to be times when you simply have to go over the threshold for dimensional weight and bear the additional costs. This is not the end of the world, though, and you should certainly never compromise the safety of your artwork simply to shave off a few inches to remain under the thresholds. Again, damaged artwork costs you far more than slightly higher shipping fees.

I will discuss how to ship larger artwork in more depth below.

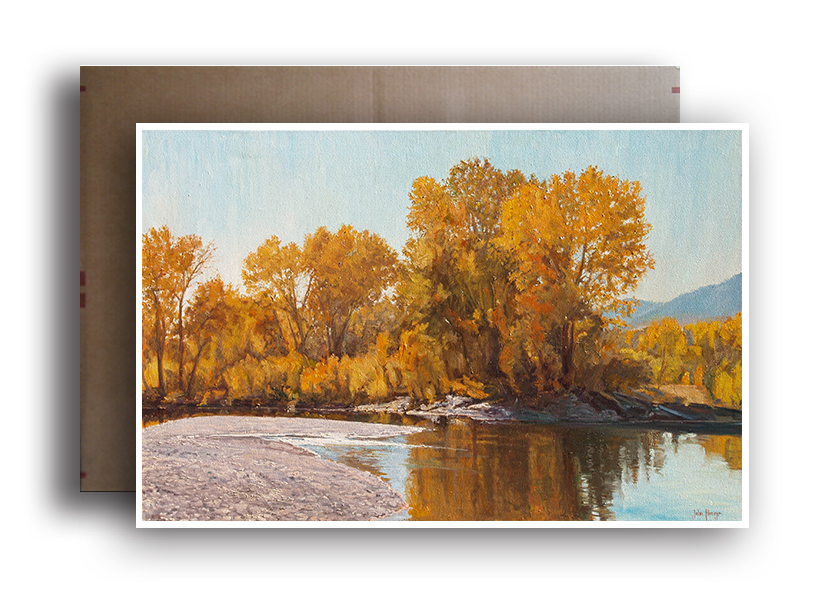

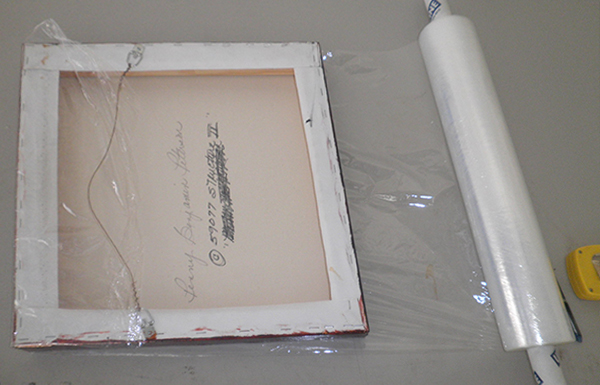

A Protective Skin of Plastic

I mentioned above that one of my essential supplies is palette wrap. I use the plastic wrap to protect paintings and frames from scratches and scuffs. There’s nothing complicated about applying the wrap, but the secret is to pull the wrap tightly around the artwork, applying pressure the entire time you are wrapping the painting so the wrap doesn’t become bunched or tangled. With our example painting at 18” x 18” we only need to go around the art once to cover the entire surface. However, with larger pieces you should pass the wrap over the surface multiple times to cover all of the artwork.

This next tip is hard to explain on paper, but as you wrap a larger piece you’ll see exactly what I mean:

Start wrapping on the back of the artwork.

Your natural tendency is going to be to start on the front, but if you start on the back and wrap at a straight angle all the way around once, you can then pull the wrap diagonally down the back side of the artwork to start your next row of wrap. By having your diagonals on the back, the front of the artwork is covered with smooth, straight rows of plastic, which not only protects the art itself, but also looks attractive to the client upon opening. It’s a small thing, but it will make the wrapping job look more professional.

Finally, and I’m not sure if this is superstition or science, carefully cut small slits in the back of the plastic so that the art can breathe. I can’t imagine breathability being a huge issue for the brief time most artwork spends in transit, but one could imagine a piece of artwork wrapped for too long having issues with trapped moisture or cracking. I don’t know if this has been proven scientifically, but I can’t see any harm in giving the art some air, so I do it.

Cardboard Padding

Now that we have given the artwork a skin of tightly wrapped plastic, we’re ready to add a thicker, stiffer layer of protective cardboard. This inner layer of cardboard is going to create a kind of second box that will greatly diminish the possibility of having a foreign object pierce or scuff your artwork. This box will also help absorb shock if the package is dropped. Most shipping companies require that freight be double-boxed before covering it for damage, and in my experience, this layer of cardboard has always satisfied the requirement for a second box.

As mentioned earlier, I always have 48” x 96” sheets of cardboard in inventory. I keep both single-wall and double-wall sheets on hand, but I almost always use the single-wall. It’s much, much easier to cut and fold, and in most cases it is more than sufficient protection. I only use double-wall cardboard when I am dealing with extremely heavy or delicate art.

You will notice that the cardboard has a grain that runs the 48” length. This makes the board easier to fold parallel to the 48” side. I try to plan my folds so that they are on this axis. Typically, the best and most efficient way to accomplish this is to have the longest side of the painting also parallel to this 48” side. You can then measure the width of the painting and double it, measure the depth of the painting and double that, then add a few inches for good measure and mark the cardboard using your T-square and Sharpie. Use your box cutter to make your cut. Now measure the length of the painting, add four inches, and cut the cardboard to the proper length (this cut will be perpendicular to your original 48” side, and therefore is against the grain of the cardboard).

Now, lay the cardboard flat, place the artwork roughly in the middle, and fold the ends over. Tape the overlap to seal the cardboard closed. The cardboard will naturally fold over the corners of your artwork if you’ve followed my instructions about following the grain.

The ends of the inner-box will be open, and because we allowed four extra inches at the end, you should have about two inches of empty space at either end. Instead of cutting and folding this extra space, simply squeeze the sides together to form a kind of triangle and tape it closed. By taping the ends in this way, you are creating an additional buffer at the end of the artwork that will act as a great shock absorber. I mentioned earlier that the edges of the artwork or frame are the most prone areas for damage, and by giving yourself this extra cushion, you have given the two ends of your artwork an almost impenetrable barrier.

Bubble Wrapping

Our final inner layer is bubble wrap. Just like we did when we were wrapping the plastic around the art, we want to keep some tension on the bubble wrap as we are applying it to the artwork. Keeping the wrap tight will allow us to maintain clean edges and prevent bunching. I usually apply just one layer of wrap to the large flat sides of the art – the bubble wrap isn’t doing much in the way of protection here anyway. Next, I almost always apply a second layer of bubble wrap around the edges of the artwork. I do this by measuring enough bubble to completely circle the edges of the artwork. I fold the bubble in half lengthwise and then tape it to the edges of the painting. For our example artwork, we would need about 72” (18” x 4”), but I would add an extra foot or two to accommodate the layer of cardboard we added and to take into account the fact that the corners will steal several inches from us due to the volume of the bubbles.

The Outer Box

Now we are ready to slide this whole, neat package into the cardboard box. We want to fill this outer box as completely as possible. The number one cause of damage to frames and corners of the artwork is movement allowed by extra space in the box. You can go about eliminating this space in one of two ways. First, you can cut the box down to size (as mentioned above in the section on sizing), or you can fill any voids with bubble wrap. Either option is acceptable if you don’t have a lot of extra space. I usually choose the bubble wrap because it takes less time than performing surgery on the box. Just keep the guidelines on carrier size restrictions in mind when making this decision.

If you do end up cutting the box down, I suggest you use your T-square and Sharpie to create straight cuts. Your box will look much better if all of your cuts are straight.

I won’t go into a lot of detail about modifying the boxes because every surgical operation is going to be different depending on the size and shape of your art. It will be easier to get good results if you tape one end of the box closed so that you are dealing with the box in its 3-D form instead of flat. If you minimize the cuts (I usually only have one continuous cut all the way around the box), you can telescope the parts of the box together to eliminate your extra space. Telescoping is great because it reduces waste and adds an extra layer of cardboard wherever the boxes overlap.

Taping

I consider sloppy taping a cardinal sin, and I want to devote an entire section of this document to the subject of taping.

The first step to good taping is to use good tape. I said it above, but it bears repeating: Use the highest quality tape you can find. Not only does good tape adhere better, it’s easier to apply.

The next secret to good taping is tension. Almost every packing tape gun allows you to control tension with a knob on the tape wheel. I suspect that many beginning shippers (and perhaps even some experienced ones) don’t pay much attention to the tension, or they mistakenly think that the tension should be minimized so the tape rolls off more easily. Low tension will cause your tape to bunch and fold as you are sealing your box, and it will also make it nearly impossible to cut the tape.

To get the right tension, I first set it to where it is so tight that I can’t pull the tape off the roll without straining, then I loosen it just a little so that I no longer have to tug to get the tape off. In other words, you want the tension just before it becomes impossible to dispense.

Applying the tape is a two-handed operation. When starting on a new seam, I hold the tape gun in my right hand and use my left hand to hold the tape down at its starting point on the box. I pull the tape gun back to unroll enough tape to cover the seam, but I do this several inches above the surface of the box. Once I have enough tape, I keep it tight, line it up with the seam, and then lower it onto the box – keeping tension on the tape by pulling the gun.

Cutting the tape is an art. If you’ve tried it unsuccessfully, you know what I mean. I once saw someone pull out a pair of scissors every time the tape needed to be cut because she hadn’t mastered the art of using the tape gun’s built-in blade.

A video, or even better, an in-person tutorial would work best here, but since I can’t do that, I’m going to do my best to describe the cutting procedure.

I want to maintain this tension on the tape, so I’m going to continue pulling the tape gun toward me. Of course, pulling on the tape gun causes it to dispense more tape, and we don’t want that to happen right now. I use my right thumb as a brake, holding the roll in place. I now have a couple of taut inches of tape extending from the box to the gun. The rest is in the wrist. I want the saw-blade knife on the gun to start cutting on one side of the tape. I’m not trying to cut the whole width at once. I make this happen by turning my wrist in a clockwise motion while maintaining tension.

In short, the tape cutting process is a combination of tension created by my thumb holding the tape roll while I pull on the gun and twisting my wrist so the blade can bite through the tape.

Piece of cake!

I encourage you to tape all of the seams of your outer box, including the short seams at the ends of each flap. This may seem like overkill, but any untaped seam is a potential snag, and if something catches under the seam, your box could easily be ripped open.

I also always apply tape all the way around the length and width of the package to tighten everything up.

Dealing with Glass

For those of you who are shipping watercolors, photography, prints, or anything else behind a panel of glass, let me first say I’m sorry. Shipping artwork behind glass is almost infinitely more difficult than shipping anything else. Glass is so susceptible to cracking in transit that some carriers refuse to insure anything that involves it.

Because the slightest jolt or tension can cause your glass to shatter, it is even more important that you provide ample padding and eliminate all possible movement.

As important as breakage prevention is, I feel it’s even more important to think about damage control. Basically, if the glass does break, you want to apply added protection so it doesn’t scratch, slash, or otherwise mangle your artwork. When I ship anything out with glass in it, I simply assume it’s going to break and then focus on making sure the shards don’t destroy my artwork.

Many shipping supply companies sell 8-12” wide masking tape that is specially created for glass coverage (it doesn’t leave a sticky glue residue on the glass when you remove it). You can apply this tape to the entire surface of the glass, and, if the glass should happen to break, the resulting shards will stick to the tape instead of slashing your artwork to shreds. 3M also makes a clear film that does the same thing.

Another approach is to get out of the glass shipping business altogether. I know of an artist who does pastels, which are, of course, displayed behind glass. When a piece is sold, the artist takes the artwork to his framer, has the framer remove the glass and replace it with a sheet of clear plastic. He ships the piece to the client’s local framer where he covers the cost of new glass. The artist has built the cost of doing this into his pricing. I’m not sure this would work for everyone, but it’s certainly an option to keep in mind.

Shipping

Now that we have the artwork professionally boxed up, we’re ready to get it on its way. There are a number of options available when it comes to choosing a delivery company, and I don’t want to endorse any one in particular. Everyone seems to develop favorites, and if you’ve found one that works for you, stick with it. If you are dissatisfied, keep trying different companies until you find one that makes you comfortable.

There are two general classes of delivery companies: the common carriers, such as FedEx and UPS, that primarily handle small to moderately sized packages, and the larger freight companies and freight forwarders that deal with larger shipments.

Generally, we will ship anything that is 30” x 40” or smaller using one of the common carriers. Anything larger will ship via a freight company or truck line.

If you are shipping infrequently, you can simply drop the package off at one of the carrier’s retail locations, give them the delivery address and let them do the rest. You will be paying retail, but you’ll also be saving yourself time and effort.

If you plan to ship in any kind of volume, however, you should set up an account with the carrier and ship using their online service. This will save you money, and often you can schedule a delivery driver to pick up the package from your studio, saving you a drive as well.

If you start shipping in even higher volume, say an average of 10 pieces or more per month, you should talk to a sales representative for the company and ask if any volume discounts are available and if they would apply to your situation. Depending on your volume, the savings could be significant.

Most of these companies offer a variety of options for delivery time. Ground shipments can take anywhere from a couple of days to over a week, depending on the distance and accessibility of your customer. You can also use their 3-day, 2-day, and overnight express services.

In theory, these expedited services are both faster and safer (the less time a package is in the delivery company’s hands, the fewer opportunities they will have to damage it!), but the costs are so prohibitive, especially for larger packages, that in most cases ground service is the only practical option.

For larger pieces you can use one of the trucking lines like Conway or freight forwarders like Bellair Express. The freight forwarders may ship the art via air, truck, or train, depending on your timing needs and budget. Unfortunately, many of these companies will only pick up from a commercial address (rather than from a private address) and may be unwilling to come to your studio, no matter how hard you try to convince them it is a business.

For more on shipping large work, see the section below on dealing with large paintings.

Some Things to Avoid

Up to now we’ve discussed what you should do to ship your art safely and effectively. Now I would like to discuss some practices you should avoid.

Don’t Allow Bubble Wrap to Come in Direct Contact with Your Art

Recently we received a painting the artist wrapped using only bubble wrap. As I mentioned above, bubble wrap is great for padding your art in transit, but it should not come in direct contact with the art.

When we unwrapped the painting, we could see that the bubble had stuck to the varnish. Removing it left an imprint of the bubble wrap on the surface of the entire painting. From certain angles you could see the perfectly spaced imprints of the bubbles. We had to have the artwork re-varnished before we could present it to a client who had already purchased it.

Sometimes when delivering a piece of artwork directly to a client, I will wrap the painting with only bubble wrap, but when I do this I make sure the bubbles are facing out so the flat side of the bubble wrap is turned toward the painting.

Don’t Reuse Ugly Boxes

Recycling is both environmentally conscious and economical, but every cardboard box has a lifespan. Avoid pressing a box into service beyond that lifespan, especially if you are shipping to a customer.

Even a new box is going to show signs of wear and tear when it arrives at your client’s doorstep. Using an old box is inviting trouble. As an artist, you want your client to feel that they are buying one of your masterpieces. You are sending the client exactly the opposite message if you show them you feel the artwork isn’t even worth the cost of a new box.

Don’t Use Styrofoam Peanuts when Shipping Paintings

As I stated in the shipping procedures section, bubble wrap is the correct material for filling voids in your boxes. Never use peanuts for this purpose.

There are two main reasons for this. The first, and I’ll admit it’s a personal pet peeve, is that peanuts make a huge mess. This is especially true when you are shipping two-dimensional artwork. There is simply no way to get a painting, photo or print out of a box filled with peanuts without disgorging them all over the unpacking area. Peanuts are very difficult to clean up – they scatter before the broom and often, if they’ve picked up a static charge, will literally jump out of the garbage can.

Second, and this is more important, peanuts don’t work in a painting box and can actually cause damage. Peanuts will settle to the bottom of the box, and as the box gets jostled about in transit, the bottom of the box will flex and expand, allowing more peanuts to concentrate there. The space at the top of the box will be left unprotected.

Peanuts are great for packing sculptures – they have no place in a painting box.

Insurance

In spite of your best efforts in padding and protecting your artwork, damage is inevitable. Once your artwork leaves your hands, it is passing into a vast and complicated shipping network with lots of moving parts. There is no way to completely eliminate the possibility of damage, so you should plan for its eventuality and consider purchasing insurance to protect against loss.

You can insure yourself against loss in several ways. First, you can buy the carrier’s insurance each time you ship a package. The delivery companies usually offer some minimal coverage by default, but this is usually just a few hundred dollars. For an additional charge you can add more coverage. You should be aware, however, that some of the companies limit their liability to $500 for fine art. Again, these policies are always changing, so it’s worth visiting your shipping company’s website or calling them to confirm their limits for fine art.

If you are only occasionally shipping, carrier insurance is probably the simplest and most efficient way to insure the work with the least hassle. If you ship regularly however, it makes sense to have a business insurance policy that covers your art not only while it is in transit, but at all times. You’ll pay far less in the long run for this kind of insurance than you will for the carrier coverage.

Talk to a business insurance agent and they will be able to get you a quote. We have a business policy with a fine arts “floater,” as well as an inland marine policy that gives us additional coverage for artwork. I’ll be honest, I don’t know what “floater” means or how something called “inland marine” protects art, but we worked closely with our agent to get the right coverage, and we have always been protected on the rare occasions our art has suffered damage.

There is, of course, another option: You can insure yourself. If you feel that the likelihood of damage is small enough, or that the cost of insurance is too high, you can simply cover the cost of any damage yourself.

I suspect most artists follow this course, and I can’t fault those who do; there are only so many dollars to go around, and insurance can’t always be a top priority. Often, damage is repairable, and since you made the art you probably have the perfect skillset to repair it!

Dealing with Damage

On the rare occasion that damage occurs, the manner in which you react will affect your relationship with your client and the likelihood that you will recover damages from your shipping company or insurance policy.

First and foremost, it’s important that you follow the procedures laid out earlier to ship the artwork safely. You are in a far better position if your client feels that you did everything in your power to protect the artwork. You are also far more likely to file a successful claim with the shipping or insurance company if you have met their shipping requirements.

Reassure your client that your are doing everything in your power to rectify the situation. There have been times where we have provided an immediate refund for their purchase and then worked to get a replacement piece from the artist.

Typically, when damage occurs, the shipping company will return the artwork to you. When the piece arrives, talk to both the shipping company and your insurance adjuster to find out how they would like you to proceed. Document the damage to the packaging and to the artwork per their instructions. You can never have too many photos or too much documentation.

Provide the shipping company or insurance agency all of the information they need in a timely manner.

Shipping Larger Works

As I mentioned in the introduction, I enjoy shipping artwork from time to time. When I first opened my gallery, I would ship everything from the smallest sculpture to the largest painting.

The techniques I’ve shared here work great for paintings up to about 48” x 48”. Any artwork larger than this almost always requires a wooden crate for shipment. In the early days of my gallery I had access to a great woodshop, and I would build the crates myself.

I felt I not only enjoyed shipping, but was certainly saving money by doing all of the work myself. Imagine my surprise when, several years after opening the gallery, I had a local art crater ship a large painting and discovered that the total charges for his crating and shipping services came to less than what it would have cost me to ship the piece myself.

Because the shipper did such a large volume of shipping, he was able to achieve economies of scale with his materials and got a huge volume discount in his freight charges. It was actually costing me more to ship the art myself, especially if I factored in the time.

You will probably find this to be the case for you as well. When shipping large artwork, it will probably ultimately save you money to find someone locally to ship the work for you. Talk to other artists in your area and ask if they’ve found someone who does a good job at a reasonable price. Unless you already have the tools and woodworking experience, it simply isn’t worth the effort to ship larger pieces yourself.

Conclusion

Shipping artwork can be a challenge and frustration, but it has actually never been easier to ship than it is today. With the right tools, supplies and shipping procedures, you can ship your artwork safely and efficiently.

What have you learned by shipping your artwork? Do you have any tips or advice that might help other artists? Simply want to share feedback on this article? Leave your comments below.

Thank you for all the effort you put into explaining the details of shipping paintings safely. This obviously took a long time to write and photograph for our benfit. You are an amazing resource for the art community. I have shipped many paintings and luckily have not had any damage, partly luck but partly putting a huge amount of padding. I always think of the old tv commerical showing a gorilla jumping on a package or a suitcase! I have made a copy of your article for my files. Thank you again.

Thanks Judy – so glad you found the article helpful!

Wow! You spent a lot of time sharing your expertise with us. Thank you! This should help save us a number of headaches.

This is a great guide by a real expert – thanks for all this invaluable advice Jason. Much appreciated.

Thank you for this! I’ve searched in the past for such a comprehensive tutorial on shipping artwork and this is the best guide I’ve seen. I’m very careful and picky about my packaging, but I do have some larger paintings (48″ x 36″ x 2″) and I dread shipping these sizes. In all cases when I ship, I’m on pins and needles till I know they arrive safely. Your article has given me additional tips I will use going forward! I’m going to keep this article saved somewhere so I can refer back to it. I really appreciate all your informative and interesting topics.

I often work with encaustic. I haven’t had to ship anything (other than carting things home from a class or studio rental) but the teachers have all recommended a layer of parchment paper on the face of the work before any other wrapping-stabilizing-cushioning materials. Nothing sticks to parchment paper. U-Line sells it flat-packed in sheets but a bakery supply place might also do that if you need it in quantity. In my home studio, I keep on hand a couple of rolls from the grocery store.

I work in cold wax and was curious about parchment vs. glassine. Anyone out there use glassine?

I have a large roll of glassine that I use. I’ve not heard of parchment (except for baking).

I’m curious too.

I’m a proponent of glassine. It doesn’t stick to anything, and is strong. It’s a good wrap on a painting before bubble wrap gets involved.

I agree with the idea that something should protect the surface of the painting before putting on the plastic wrap. I always use a sheet of glassine….available through ULine.

Thank you so much for this article I am always worried about shipping my large pieces and I have considered shipping canvas only and unstretched but have never done it. I love your articles and enjoyed visiting your gallery in person. My cousin Chris (head chef) lives there and recently opened a new restaurant called the Craftsman.. It’s awesome.

Thank you for such a much needed article that I

usually don’t think about.

I am planning on having my first exhibition in Paris several years from now. I will be shipping framed and unframed pieces. Is there a way that I can bring my packaged art directly to the airlines and have the gallery pick them up on the other end? Or me fly over with the art and arrange to help the gallery with the setup?

Jason. Can you give us some resources where to buy things like cardboard? Thanks.

We are currently buying most of our supplies through ULINE, though if you can find a local packaging supply provider it may be more economical. ULINE is nice in that they have just about everything you could imagine, and have locations around the country that provide quick shipping.

Thanks so much for this tutorial-excellent. I used to be able to buy cardboard sheets from a local company but they no longer do a retail with individuals. Uline has a minimum amount plus shipping fee. That cost plus a shortage of storage area makes them impractical for me. I wonder if others have suggestions. I am able to buy some boxes from a Goin’ Postal store. I’ve become a hoarder of any good cardboard which sometimes feels more precious than the art. :- /

I’ve been buying cardboard single wall cardboard sheets from Grainger in 5-sheet packs. They’re in small quantities, sizes that fit in the back of my little SUV, acid free and easy to handle. So far so good. Double walk is also available. There are lots of Grainger outlets everywhere so IF you can pick up, you’ll save on freight.

Thanks Greg, I will check them out!

Thank you so much for this article! I am currenlty researching ways of sending my artwork. I sent three small pieces of artwork to Spain a month ago via USPS and unfortunately the parcel is held at customs, and I am at a lost at what to do! Any recommendations here?

I am aware that I need to find another carrier, but USPS seemed appropriate since I wasn’t sending any canvas or frames, only paper artwork so a nice envelop did the job. But I am so worried about the parcel being stuck in Madrid! There may be a lesson to learn from here…

Hi Marta – I’m not sure about this, because I’m not an expert, but here are my thoughts – 1st in the future, make sure you have a customs declaration on the outside of any package, including an envelope, containing artwork – this is similar to and almost identical to a “Certificate of Authenticity” but you can check online for exact details of what it must state.

And as for your current package stuck in customs – I’m afraid that the only answer I can think of is for you to contact a freight forwarder in Madrid, ship them both the exact shipping label you used on the original package, a package description – size, weight, package color, and a custom declaration for the work that is stuck in customs – the freight forwarder can then go to customs, have them find the package, present customs with the declaration, and get the work cleared through customs – which then will possibly allow it to proceed via its original shipping route (postal service) or be released into the hands of the freight forwarder as your agent, who will then compete the delivery for you. This may be somewhat expensive (but perhaps not prohibitively so – maybe on the order of $100 -$300, which depending of the value of the artwork in both real $ amounts, and emotional value, and the value of not losing a customer, may certainly be worth it – I would find a freight forwarder in Madrid and check the cost before just assuming it would be too expensive, because it might not be) – but it’s probably the only way to get the work to clear customs, where otherwise it will remain…..forever. They will not send it back to the shipper (you) or let it move forward until their requirements are met.

Thank you for taking the time to provide this invaluable information!

This was very good info. U-Line is a good source of packing material.

I am guilty of using boxes too many times, I have quite a collection in the garage. Most of my shipping is to shows, not to clients, though.

Thank so myou uch for this article. As a pastel painter, shipping is a real challenge.

Thanks for the wonderful, detailed information – it will save me a lot of trial and error when it comes time to ship artwork!

Great article! I have found a framing shop that will pack and box my paintings and giclees plus deliver them to the shipper or arrange for pick up. They have the materials, equipment, etc. to create the boxes so I don’t have to and their prices are reasonable.

Virginia – this is actually the best possible solution for artists, because it’s one more roadblock removed from the best use of an artist’s time, which is – creating art!! Everything else is just an impediment, and the more of them that can be removed the better!

Great article. Lots of truly useful info and hints. Thank you.

Thank you Jason for these many, and timely, pointers. I hate packing and promise to l

improve on my performance from here on in. And thanks to Melanie Hulse for her tip on encaustic work.

For small paintings 18 x 18 and under, I use blank pizza boxes. I add my branding with labels and stickers. For larger ones, I use mirror boxes from Uline that come in 4 pieces and can go together to fit up to about 40 x 40 inches. For larger than that, UHaul sells mattress boxes. So far none of my pieces have ever been damaged in transit, and I’ve shipped over 400 to people in 15+ different countries. And yes I have friends who work for both Canada Post and UPS who have told me “fragile” means “kick harder”. Especially if using regular mail, the post office has no different standards to handle anything marked “fragile”. Same with “Do Not Bend”. It’s up to the sender to make sure things that are fragile are packed properly and that things can’t bend. I learned that the hard way when I sold my first run of prints in 2015 lol

Thank you for providing the detail of your experience! I have shipped many pieces on frames with glass and hold my breath every time. I will definitely use your pointers in the future.

Hi Jason, I almost didn’t read this as I don’t ship paintings, but am glad I did. Much of your advise and the technique will work well for shipping some of my mosaics. I’ve been contemplating how to safely package and ship mosaic mirror frames that have a looking glass mirror piece in the center and I like the idea of the protective layer over the mirror to protect from scratches and heaven forbid, shattering. (That did happen to me on the very first mirror frame I sent!) Plastic wrap, then bubble wrap, then cardboard, all before snuggling the piece into the outer box is great. I’m sure that I’ll triple box my pieces using this technique.

I look forward to you completing a shipping blog for sculpture as I think most of my work will better fit into that category. Thank you for such great information!

Thank you so much. Very informative.

Jason,

As always thank you for a wealth of information. I have enjoyed reading this post because I paint large-scale paintings, some of my work is 9ft x 15 ft. So, I’m very happy to learn from all of you.

Adam, the U-haul mattress box is an amazing idea, I will look into it.

This article is full of some well-researched information. You have made valid points in a unique way. After reading this article I get to know more about rigid box and packing material or things

I’m shipping my very first non-local painting purchase today. Thank you for this outstanding article. It’s going into my reference “file”!

Excellent article. I was curious that you mentioned a 48×48 inch painting as the largest to pack in a cardboard box. That is my largest size but I cannot understand how to use the largest telescoping box that ULine offers, which is 48×36. If 48 is the max on one side, how would you fit in the packaging materials?

Thank you.

I’ve telescoped 4 boxes together on both the length and the width. It’s a pain but it works, and offers additional cardboard protection.

Thank you for this info. I have a question about return labels. The galleries want a prepaid return label shipped with the painting. But what if I sell the piece and it does not have to be returned. How do I get my money back from that label.

Thank you,

Alison

Alison, shippers like UPS will not change you the return cost unless the return label is scanned, so you don’t have to worry about getting the money back.

thnks

Thanks for all the tips Jason. Always appreciate your articles. Wanted to share a life saving box on the market called Air Float. Basically it is a plastic lined box inside of another box with foam inserts. At the purchase site you type in the dimensions of the painting, the box suggestion is usually about 3 to 4 inches larger than your painting. You cut the perforated foam to your paintings size and then place the top foam on top. I placed clear plastic over my painting just like you. This box saved my painting when shipping my painting to a museum show recently. I shipped it FedEx 2 day air a week early from deadline. I figured 2 day air meant less handling. They lost my painting, it went by truck and then finally air. Took 8 days to get to museum. Just in time. Good news the painting arrived in excellent condition. Draw back for the Air Float System is that it cost me $120. However FedEx charged $170 for shipping after 3 weeks got it reduced to $110. After all my painting went through and made the trip safely, I would highly recommend the Air Float system.

Thank you so much, Jason. Your articles and webinars are always so jam-packed with useful information. Much appreciated.

Great advice for shipping paintings, Jason. I’d love to see your thoughts on shipping stone sculptures. Thanks.

Nice and timely. Just the other night I was looking at U-line and other box suppliers. I bought a couple of their ‘Delux Artwork Shippers’ that are dang expensive. But after reading your article the ‘Large Side Loaders’ or the ‘Telescopic Boxes’ would save money but not time. Boxing is something I dislike spending time and worry on but I feel better after reading your article. Thanks for the information and the time put in.

Thank you for this excellent detailed tutorial on shipping art. I very much look forward to your information about shipping sculpture. One hard-earned lesson: make sure you know what a shipper’s insurance includes. Recently a shipper changed how it packed and a sculpture was damaged. Only the shipping was covered, not the packing. Ouch. We work with other shippers now.

This is the most complete, detailed, and useful set of shipping instructions I’ve ever come across anywhere!! Thank-you for its clarity and detail, and even though I know most of the things covered, I’m saving the article to re-read before I ship new works, because it’s so easy to overlook something, or get careless and not bother to do it!!

A couple of things I’d like to add about shipping photographic works – If possible I ship all my prints unframed, rolled, and in a tube. I have never had a problem with a print sent rolled in a tube, either being sent by me or being received by me when shipped by a non-local photo-lab to me. It’s important to use a heavy-duty, thick walled tube and not just an average “mailer-tube” you might buy in Staples – but these can be purchased online very easily, and are not too expensive. If for some reason, you can’t get a thick-walled tube, then do the following – after the artwork is packed in the thin walled tube, pack that tube in a cardboard triangular box that is just large enough to surround the tube – this will produce a very strong package even out of a thin walled tube

But in the cases where I must ship a framed work, I NEVER use glass. I frame the print using non-glare acrylic instead of glass. This can be fairly expensive for a larger work, but the cost is far far less than the cost, aggravation, or loss of a good client relationship, of having to deal with a damaged work being received by a client. And in addition, non-glare acrylic really is SO MUCH BETTER for viewing an artwork. Glare is the most distracting thing you can possibly do to an artwork other than throwing ink all over it. [for this reason, I never have prints made with a glossy surface by a lab (matte or satin finish only), and I am very very against metal or glass prints that some photo-labs are always advertising as so incredible – they are not!! – galleries have very elaborate lighting systems just to avoid this problem – most people’s homes do not – and that is where your work most likely will eventually hang] So if you need to ship a framed photo, or watercolor or other work on paper, spring for the non-glare acrylic nosed of glass – you will never regret it!!

Jason, what a great resource for those of us who ship work sporadically and struggle to remember what we did the last time 🤨! Thank you for your generous sharing from your years of personal experience. My painting pieces are made from broken chipboard with intentionally ragged and fragile edges, meaning that even more care must be taken to isolate any shifting movement. Though they’re wood, I think of them as raw eggs going through the mail.

Great article! Just one thing to note. When you ship using FedEx Express, the Airbill has a question asking if you want to declare a Declared Value on the package. If you do declare a value, there is an additional charge for each $100 you declare. Please note, Declared Value is not insurance! It would be the possible amount paid if the package is lost or the damage is deemed to be the fault of the carrier.

Thank you so much for all your excellent and extensive advice!

I look forward to your advice on shipping sculptures, too.

Linda Wren

LWrenCeramics.com

Thanks for the informative article. I typically paint on canvas board, and when I have sold paintings from off of my webpage, I do not sell framed paintings (which makes for a simple packaging process). However, I have recently used your ideas to begin to get my work into local galleries, which require the paintings to be framed. So far, I have hand-delivered the paintings. Oddly enough, none of thoe galleries have specified any packaging requirements for shipping. I have recently been accepted into a juried show, and will need to package the framed painting. I’ll be sure to mark the packaging with my name and the title of the painting, so that the gallery can keep the packaging set aside for the painting.

I recently received a commission for a 40” x 60” painting. Is there any information on removing a painting from the stretcher bars for shipment? This would be an acrylic painting, and not textured by impasto. TIA.

How can we say THANK YOU! Thanks so very much for this detailed information.

I have one further question onto this. Anyone is welcome to respond.

HOW DO YOU SHIIP OVERSEAS OR OUT OF COUNTRY? Thanks

Glad it’s helpful Eileen. Shipping overseas is very much the same as domestic shipping, but with more paperwork! We package in a very similar way, though we do sometimes try to add a little more padding and packaging. An international shipping broker or company can help you with the paperwork.

Thank you for this very extensive and detailed article. The photographs were especially helpful. I ship my framed oils and watercolors using the double box/bubble wrap method and always use an interior wrap of white paper to protect the surface of the painting and frame from the bubble wrap. It makes a nice presentation, too, when the customer unwraps their art. For shipping prints, I always use Uline’s mailing tubes. They are very sturdy, and I have never had anything damaged.

Thanks again for this very useful article.

Thank you for your kind words and helpful suggestions!

Thanks for your thorough packing information and the relevant photos.

My only concern would be that the clear plastic wrap in the first step might adhere to the thick paint or to the surface of the painting being shipped. Always enjoy your posts about the art business.

Thanks Al – you would definitely want to make sure whatever is touching the surface isn’t going to affect it. We’ve found that this heavy duty plastic doesn’t adhere, but you’ll see in other comments that alternate materials are suggested. The nice thing is that once you figure out what works best for your work, you can stick with it and have a systematic approach to shipping your art.

Hi Jason,

First, I want to thank you for Red Dot Blog which I follow religiously and this invaluable guide to shipping art. I just shipped three paintings to my gallery and one had gotten the floater frame dinged. So if a client is interested in purchasing, we will probably have to make an adjustment in the price.

This particular painting is only 12×12 and wrapped in palette wrap and sheets of soft foam! Sometimes you have to believe the shipper is trying to push one’s packaging to the limit.

At any rate, I will follow some of your guidance

and make my boxes stronger in the future. Thank you again!

Thank you so much for your kind words and for following RedDotBlog! I’m glad my guide was helpful to you in shipping your art. I’m sorry to hear that one of the paintings arrived with damage to the frame. That can be very frustrating.

If you’re selling the painting as is, I would recommend being upfront with potential buyers about the damage and adjust the price accordingly – in other words, don’t wait for the client to point it out. We wouldn’t want someone to buy it and then notice the damage later and think the gallery was trying to pull one over on them.

Thanks Jason for this great post on shipping. Two things came to mind for me, one is your examples in the photos are unframed work, but most work is framed, and that usually adds another two inches to the depth of the piece. Do you use a box that has the same clearance from the frame depth or just clearance form the artwork itself.

The other important note is that I have been told by a number of people that if you are the artist shipping the work to say a gallery for a show, and damage results, places like UPS and FEDX only reimburse you for “cost” not the value of the artwork. So you would only recoup framing and materials cost. Have you heard that? If true most artists can save a LOT of money not insuring their work sent to be in galleries or shows by not insuring for the value of the art. Insurance is usually the biggest cost of shipping.

Tom, I have the same question about shipping framed work. Does the process change at all?

Great points and question Tom. The process is similar with framed work. We do still work to give the art, including the frame the suggested clearance. The frame is going to further help avoid damage to the artwork, but if the frame itself is damaged, I would hope to have the carrier pay for the repair or replacement of the frame.

You are correct about replacement value coverage from the freight carriers. I don’t want to get into the technicalities of what that might mean in individual cases, but make sure you have a conversation with the carrier before you spend a lot on carrier insurance that might not end up covering you the way you thought it would. We carry a commercial insurance policy for exactly this reason.

Thank you for taking the time to prepare this article. Shipping is exactly the issue I am struggling with now. Your advice about packaging was very helpful. I am shipping a larger painting and FedEx and UPS costs are high— I appreciate the suggestion of other shipping services to consider—i will also ask around at some local galleries.

I am about to ship a 24x48x2 acrylic painting. Can I use freezer paper to cover the surface of the painting rather than the plastic wrap ?

That’s one I’m not sure about – you would just want to make sure the paper doesn’t have any residue that would adhere to the surface of the art.

This is great, thank you, Jason! I actually pack my work pretty close to this (I’ve use glassine paper instead of plastic wrap for the first layer). I’ve double-boxed but not your way, and that makes so much more sense! I read this article on shipping paintings – thinking about adding this foam board to my packing but can’t imagine using only that (although this artist has shipped loads of work this way) – https://www.davidlangevin.com/blogs/news/shipping-paintings

Thanks for the info!

Thank you for the great post on shipping artwork. I am going to share this with all our gallery shipping crew. Some of the best advice ever on safely wrapping and packing artwork.

This was a very informative article Jason, thank you for publishing it. I am eagerly awaiting the follow up article on 3D art, as I am a ceramic artist. I’ve recently developed a series that has captured the attention of a particular gallery I would love to get into. The gallery owner and director both love the art but have strong reluctance to shipping these pieces. I am working on solutions now. If you’d like a case study for your upcoming “shipping 3D art” blog, I’d be happy to share with you; maybe even collaborate!

I am so grateful that you, a gallery owner, is so willing to share your knowledge and experience with artists. Truly you see the value in creating win-win situations. Thank you.

Hi,

Very useful article. What you think about taking canvas off from stretchbars and Sending it rolled?

Amazing valuable information, Thanks Jason!

Thank you. 2 comments:

I have used pirateship.com for great discounts at ups. The tip was given to me by a ups store clerk!

The idea of poking holes in your wrap makes sense. In my former life, I was a scientist for a steel company. Steel for automobiles has to be shipped and arrive with no visible surface issues. From Indiana to Mexico the steel and your artwork may cross the continental divide with significant temperature, pressure and humidity changes, so breathing is important. I imagine a painting has the same considerations.

It cost more in materials and is a bit heavier so increases the cost there, but I like to put a sheet of 1/8″ masonite under and on top of the painting just before putting the wrapped and padded painting in the box. I usually do this only for stretched canvas’. It could save a tool puncture from going through the canvas.

Oh my gosh! Jason, this is AWESOME, and so very helpful! You mentioned every detail possible…and more!

Thank you so much!

You are so generous with what took you years to perfect. On this subject and so many other subjects as well.

Thanks for sharing! Earlier in my career, I was an exhibit designer for an art museum. I got to work with conservators and art shipping companies and saw the amazing effort that museums went to when shipping a work of art. I’m talking custom built crates with foam cutouts and silica gel. It was always exciting to crack a crate open and begin to work my way into the packing to reveal the masterpiece or rare artifact. As a result, when I ship my own paintings, I tend to over engineer the shipping. I am also very aware of the unpacking experience. When a collector opens the box, the unpacking experience should be exciting and elegant. I incorporate carefully labeled instructions throughout the packaging, heightening the anticipation with each layer opened. Good article!

Great article Jason.

I’m looking forward to your article on packing and shipping sculptures. I’ve been a clay artist for over fifty years and make most of my own shipping crates. I value your generous information.

Thanks again for all you do for the artists of the world!

Thanks a lot for your helpful article and all the given details.

You didn’t mention mailing tubes (sorry if this isn’t the right word, I am German). Is there a reason? We usually took the canvases out of the frame and shipped them rolled.

I am very interested in this, as well. My customers request this, as it is less costly to ship and have restretched (although, I have also seen extra charges from carriers for tubes?). I am still unsure of cost to ship larger art. Honestly, it intimidates me.

Thank you so much for all of the detailed information that you provided about protecting and shipping artwork. I own a frame shop and a newer art gallery. Shipping has always frightened me, and I have been reluctant to offer it, which I know is harmful to my overall sales. I’ve always wanted to know if it’s customary for the gallery to pay for shipping of an artwork or does the collector pay for it? Most of our sales are conducted in person in the gallery. However, recently, I have sold some pieces online and have had people buy art in person, but they want it shipped to their second home. Naturally, I think the client should pay for shipping since they have the opportunity to pick the art up in person, or take it and ship it themselves. Recently we shipped a 36×48 gallery wrapped painting. We put it in an art plastic bag (that we use in our frame shop and is sold by a large moulding supplier company) and then put bubble wrapped plastic corners on it. We then took it to UPS to be packed and shipped. It was only traveling 150 miles and it cost $297.00. The art piece was sold for around $2k. This customer could have picked it up in person, but choose not too. If this was your gallery, would you have absorbed the shipping fee? Keep in mind that we are at a 40% commission rate.

Thank you!

Best column I’ve read, Jason, and I have been following RedDotBlog for more than 15 years. Thank you so much for such detailed packing advice. Knew never to use styrofoam peanuts, but the packing advice is excellent.

Wonderful! Thank you so much. I especially appreciated the bit about using a tape gun.

Thanks so much Jason!

I was thrilled to recently sell a 24×36 mixed media piece to someone who lives in another state. I was stunned to discover that UPS only insures for damages if they do the packing. The cost of packing and shipping including insurance was $237. I ended up sharing the cost with the client but felt there were no safe alternatives. Makes me think about building that cost into the price.

Thank you Cynthia. I have been packing and shipping for a long while but most of your comment was news to me. Such an important set of details for all of us who sell, buy and ship art or need to do this.

Absolutely wonderful! You really are a great instructor and writer! I love all the responses, too, and have saved this article to my “shipping” files to keep forever.

I have a concern as to how or when do I charge the buyer for the cost of shipping? Should I estimate a percentage and add it to the price of the art? How would I know what that will be? Should I inform the buyer (next to the price) that shipping is going to be 15%, 20% ? or how would I include this somewhere? Large pieces that need special crating might be very expensive–I’ve been shocked when I’ve had to absorb some of the cost. How do you add the cost of shipping?

Thank you for helping with this “enigma” !

Hi Jason – this information was very helpful. I have a large acrylic painting packaged and crated ready to ship from the east coast to Phoenix, AZ. Since temperatures in Phoenix are currently hitting 116 degrees how can I make sure the painting won’t be damaged from heat?

Great advice.

One tool I find useful is a heavy-duty plier stapler. The lower jaw slips between two cardboard layers. I use it on folded box corners on the outer box and on closing the ears you describe on the inner box. The staples are heavy duty and come in several lengths.

The pallet wrap sounds interesting. I currently use Tyvek house wrap suggested by another artist. It “breathes” so I don’t have to slit the wrapping containing the art work. Paint doesn’t stick to it. But, it is very slick making it hard to hold onto a package you are wrapping. I suspect it is also more expensive than pallet wrap.

Thanks for all the great info!

Shipping is my least favorite part.

Thank you so much for all this wonderful information, it’s certainly helpful, as in the past I have found the delivery part very daunting. I have been an artist for over fifty years and love what I do and I am so thankful to do what I love.

Recently I have received so many orders for my art from USA and England, as I live in Australia I was overwhelmed by the thought of the Delivery costs and packaging that I said no to the buyers, presently I have several hundred works stored which are canvas, paper and framed works and I need to find a way to sell this lifetime work. I feel so lucky to be a creator and to have received awards and sales, looking forward to the next challenges in my journey.

Thanks again for all your time and effort and passing on this valuable information.

Regards

Lorna Gerard

Wow! This information was invaluable to me. The detail of the instruction is terrific. I have to ship eleven pieces of large art to auction in New York City. Thank you, very much.

This is my biggest problem when looking into galleries outside of my local area. My work is expensive to ship. It is under glass and it is large. Generally one piece costs up to $150 to ship. I’ve got a shipper that packs well and nothing has ever broken. I have limited myslef to galleries or exhibits where I can drive for delivery.

Hi Jason,

Thanks for your very helpful and thoughtful discussion. I have a question, please. I know of some artists who ship large paintings rolled and inside a cardboard tube. What do you think of that method and if you have used it can you describe the process, please.

Thanks.

Rolling and shipping in a tube can work, Hal, but it’s not my preferred method because it creates risks for damage and adds an extra step for the buyer to re-stretch or mount the piece. Crating stretched work tends to be safer, though more costly. I’ll plan to put together a step-by-step on this in a future post.